This article was originally written by Jikun Huang in Mandarin and published by Peking University. Read the original article here.

Founding

The story of the China Center for Agricultural Policy (CCAP) started with my encounter with Scott Rozelle in the Philippines in 1988. Then a Ph.D. student at Cornell University, Scott attended an international conference hosted by Dr. Cristina David, my advisor at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). This chance encounter started our collaboration that has lasted 30 years and continues today. We both completed our graduate studies in 1990: Scott began teaching at Stanford University, while I started my postgraduate work at IRRI after receiving my degree from IRRI and the University of the Philippines, Los Baños (UPLB).

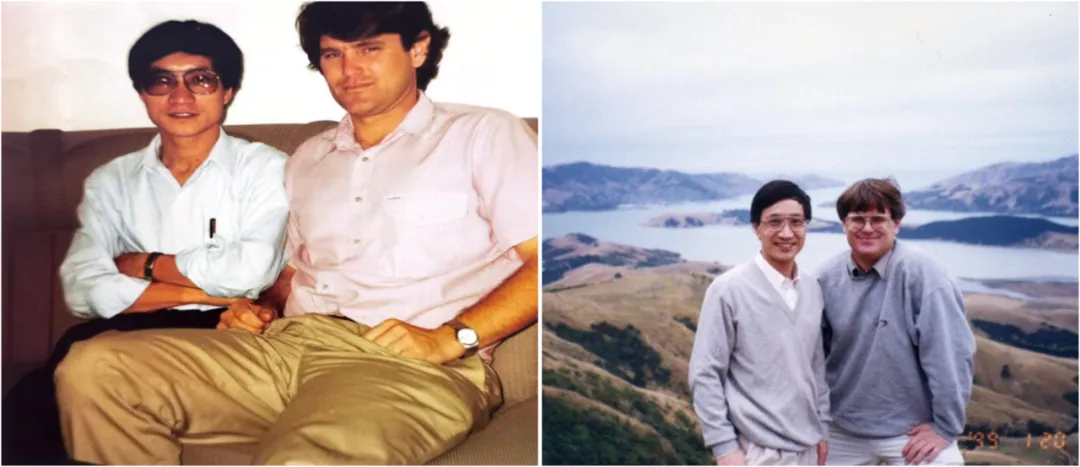

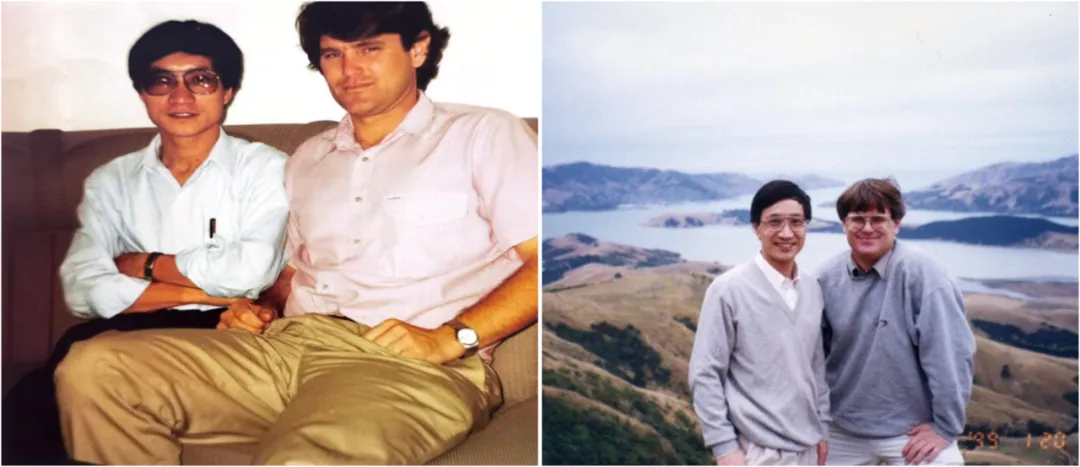

Jikun Huang and Scott Rozelle.

Between 1990 and 1992, we submitted a joint project proposal to study China’s rice economy to the International Development Research Center (IDRC). I returned to China in 1992 and initiated the project with Scott at the National Rice Research Institute under the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS). Besides producing many important findings, the project helped us discover a cohort of talented scholars, including Yongzhong Qian, Ting Zuo, and Ruifa Hu, who later became my Ph.D. advisee at Zhejiang Agricultural University. Scott and I have since become not only collaborators in research, but also mentors and friends to each other.

The agricultural economics project team in 1992.

The decision to establish CCAP was deeply informed by my experience at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). After being promoted to become the youngest principal investigator at CAAS in 1993, I joined IFPRI to conduct research on its 2020 Vision Initiative. During my time there, Lester R. Brown, founder of the Worldwatch Institute, proposed in his famous opinion piece that “China could starve the world in 2020.” I felt compelled to rebut his claim and, inspired by IFPRI’s framework for agricultural policy research, sought to establish a research institution for agricultural policy in China. My idea received support from Scott and Dr. Xigang Zhu, then director of the Institute of Agricultural Economics at CAAS. I also contacted Linxiu Zhang, my colleague at UPLB, and Ninghui Li, a collaborator of IFPRI, to enlist their support. When my decision finally reached Dr. Per Pinstrup-Andersen, then director of IFPRI, he felt surprised by my decision to return to China but excited by the prospect of my establishing a “mini-IFPRI” there.

I travelled back to China in August 1995 and started preparing for CCAP in September. Our first office was two small rooms on the first floor of an unassuming two-story building in the computation center of CAAS in Beijing. In the rooms were computers, files, and a laser printer I purchased in the U.S.– since then it had served us loyally for years, only retiring when we relocated out of CAAS. The team at the time included me, Linxiu, two graduate students, and a research assistant. With help from Scott and Songqing Jin, my assistant at the China National Rice Research Institute, CCAP’s work began in fall 1995.

The first months at the office were sprinkled with many fun and memorable moments: I gave the students a budget of 500 CNY to buy a thermos so that we can drink hot water in the office; They brought back an electric kettle with a button-operated dispenser, a luxury item that turned out to be our most trusty office appliance.

After about six months in the small office in the computation center, we relocated in the spring of 1996 to an office in the Institute of Agricultural Economics. The Institute offered a suite of four rooms to accommodate our team, which grew with the joining of new scholars, including Ruifa Hu and Ninghui Li. With newly acquired funding, we equipped our office with state-of-the-art infrastructure, complete with corner desks, swivel office chairs, and cubicle dividers. Even our logo, which we designed ourselves, stood out at the time for its creativity.

The center’s administrative structure was also innovative for its time. Thanks to support from my mentors and the senior agricultural economists at CAAS, like director Xigang Zhu and Dr. Fangquan Mei, the center remained financially independent from the Institute. Its staff received an annual salary, and its expenses were managed independently to allow for more efficient allocation.

In May 1996, the center was officially named as the Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy. Our first large-scale field research in rural China began that summer and lasted for over a month. For many of us, this was our first foray into standardized field research, and it left a lasting impression: Many of the children we surveyed dropped out of school due to poverty. In 1997, I proposed that we pool a research award the center had received and a proportion of our wage together to start a financial aid program for children struggling with poverty to stay in schools. The proposal was warmly welcomed by my colleagues and collaborators. On our behalf, education officials in Xingguo County in Jiangxi Province subsidized the education of children from low-income families in the county and purchased stationery for them. The program lasted 15 years until the government initiated its poverty-alleviation initiatives in the 2010s. Many of the beneficiaries attended college, and some even completed Ph.D. degrees.

CCAP’s work quickly accelerated after the establishment of the first Advisory Committee in 1997, with Scott as its chair and 12 renowned scholars from 10 countries, including Professor Yifu Lin at Peking University and Dr. Shenggen Fan at IFPRI, serving as members. In January 1998, we initiated a project on the challenges and strategies of China’s grain production in the 21st Century. Inspired by IFPRI’s framework, we focused our research on four areas: agricultural technology, food and agricultural economics, resource and environmental economics, and rural developmental economics. Our projects examined China’s agricultural technology and innovation, rice production, pesticide use and conservation, industrial policy, land rights and the labor market, the grain market and agricultural subsidies, water resources, and rural public goods.

As our projects grew, so did the number of late nights at the office. I was fortunate to have the company of my family in Beijing from the summer of 1996, while many colleagues split their time between conducting fieldwork in rural communities and cleaning data in Beijing. We often stayed up in the office, writing research reports until the security guard locked the gate to the building at midnight, and had to ask to be let out. On several memorable nights when even the guards had left, we resorted to exiting from a second-floor window and sliding down the tree outside.

The team expanded, too. Dinghuan Hu and Zhenyu Sun joined in 1998; I invited Jintao Xu, who had just finished his studies in the U.S., to join after meeting him in Singapore in 1999; In 2000, Luping Li joined after graduating from UPLB. The center also enrolled over 30 graduate students between 1997 and 2000 and hired a growing team of dedicated administrative and research assistants to support them. Many of the assistants went on to pursue degrees at universities abroad. Besides Scott, the center also hosted international scholars like Don Antiporta, Carl Pray, Loren Brandt, Chunlai Chen, and students like Albert Park, Bryan Lohmar, and Xiaoyong Zhang. Outside of our research, we organized many gatherings and outings to bring the growing team closer together.

Our work soon paid off. To our pride, two projects were awarded by the Department of Agriculture for advancing agricultural technology between 1996 and 1999, and our center and I also received numerous awards for contributions to agricultural technology and China’s food security.

The center’s first five years at CAAS laid the foundation for its development in the following 25 years; Despite the center being restructured as part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) later, the collaboration with CAAS continued, and its use of fieldwork to inform agricultural economics research still influences us today.