Fertility Fell Sharply in China Recent Decades; the One-Child Policy Explains Only Some of the Drop

Fertility Fell Sharply in China Recent Decades; the One-Child Policy Explains Only Some of the Drop [ 5 min read ]

Insights

- Using census data from nearly 4 million women in the 1980s and 1990s, researchers identify the effect of the one-child policy (OCP) by comparing fertility patterns of Han families who were subject to birth restrictions, with ethnic minority families who were largely exempt.

- The OCP is responsible for an estimated 38% of China’s fertility decline. The effect was sharpest among urban and educated women, who faced higher non-compliance costs.

- The remaining 62% of China’s fertility decline was likely driven by broader social and economic forces — such as rising education levels, rapid urbanization, and higher child-rearing costs — rather than the OCP itself.

- Because these pressures remain, the lifting of fertility restrictions in 2021 is unlikely to significantly boost birth rates.

Source Publication: Hongbin Li and Xinzheng Shi (2025). The effect of the one-child policy on fertility in China: identification based on difference-in-differences. Journal of Population Economics.

Read this brief on SUBSTACK

China’s one-child policy (OCP) may be the largest social experiment in human history. Launched in 1979, the policy limited most households — especially in urban areas — to a single child, with women assigned birth quotas and families punished for “above-quota” births. Over the next four decades, the policy shaped the lives of more than one billion people in the world’s most populous nation. In 2021, the government abolished all fertility restrictions to counter a rapidly aging population, a shrinking labor force, and a persistently low birth rate that threatened economic growth. But how much did the OCP itself reduce fertility in China, and what are the prospects for a rebound now that the restrictions have been lifted?

The data. The researchers use two large samples from China’s 1982 and 1990 Population Censuses (covering nearly 4 million women aged 2064) to study OCP’s effect on fertility. Because the policy applied strictly to the ethnic majority Han Chinese but not to most of China’s ethnic minorities, the authors compare changes in fertility between similar Han and minority households to assess how much the fertility decline was due to the policy, versus other factors. Any extra decline in second births among Han relative to minority households more precisely identifies the true impact of the OCP.

A social experiment affecting a billion people. China’s OCP limited most families to a single child through quotas, fines, and strict penalties. Enforcement was particularly harsh in cities: fines could take up to 70% of a monthly salary, and parents with extra children risked losing their jobs or promotions in state-owned enterprises, the dominant urban employers of the 1980s. Above-quota children were barred from subsidized public schools, effectively excluding them from quality education. At the same time, local officials faced career-ending demotions if their communities exceeded birth quotas, sacrificing both income and future promotion prospects, which gave them strong personal incentives to enforce the policy. Rural areas typically saw one-time fines for above-quota births — and in some places a second child was allowed if the first was a girl. The policy mainly targeted Han families, while most ethnic minorities were allowed two or more children in the 1980s.

The policy accounts for only some of China’s fertility decline. During the 1980s, fertility in China fell sharply: the probability of women having at least two children dropped from 95.5% to 66.8% (a 28.7-percentage point decline, or nearly a one-third reduction), while the average number of children per woman fell from 3.8 to 2.9. The decline was steeper among Han women subject to the OCP. Compared to ethnic minorities of similar background, Han women were significantly less likely to have a second child: in the 1982 census, the policy reduced their chances by an average of 7.5 percentage points (from roughly 96% to 88%), 9 percentage points for women born 1945–1959, with the largest gap in the 1958 cohort, where Han women were 23 percentage points less likely than minorities to have a second child. By the 1990 census, the average effect on second births was 11 percentage points (Han women about 67% versus 78% for minorities), accounting for about 38% of China’s total fertility decline in the 1980s, with the strongest impact on women in their prime childbearing years.

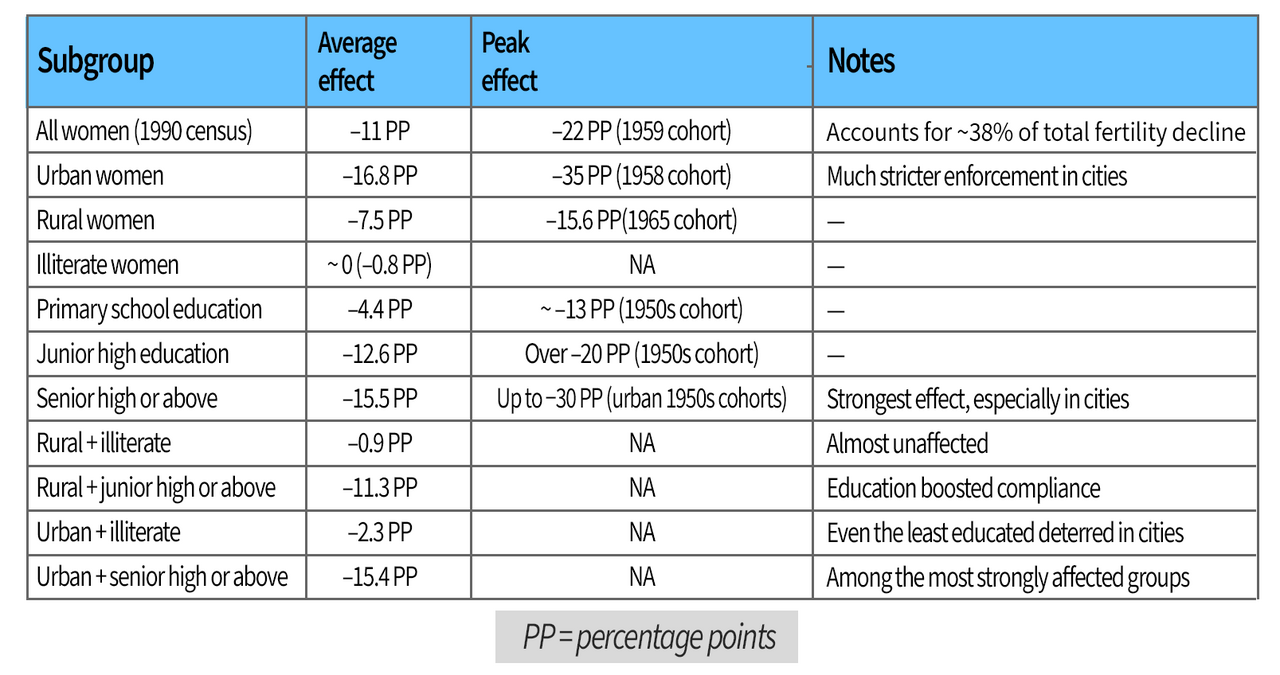

The decline in fertility was sharpest among urban and educated women. The OCP’s impact varied widely by both place of residence and education. In cities, the probability of a second birth among Han women fell by an average of 16.8 percentage points, compared to 7.5 percentage points in rural areas. The effect reached a dramatic 35-percentage point drop for urban women born in 1958, while the peak rural effect was only 15.6 percentage points for the 1965 cohort. Education also mattered: the policy’s effect was negligible for illiterate women (a 0.8-percentage point drop in second births), perhaps because enforcement was weaker in the countryside, children remained important for farm labor and old-age support, and the opportunity cost of childbearing was low. By contrast, the effect on second births was much stronger for educated women — a 4.4-percentage point drop for those with primary schooling, versus 15.5 percentage points for senior high or above. When looking at education and residence together, the policy curbed births in rural areas by 0.9 percentage points among illiterate mothers and 11.3 percentage points for those with junior high schooling or more. In urban areas, the policy curbed births by 2.3 percentage points among the illiterate to 15.4 percentage points for women with senior high schooling or above. Overall, the results show that the OCP was enforced more rigidly in cities and that higher education amplified compliance, especially in urban China.

Likelihood of having a second child by residency and education level

The end of birth restrictions is unlikely to significantly boost fertility. The study shows that while the OCP significantly reduced fertility, it explains only about 38% of the overall decline, with the remaining 62% likely driven by broader social and economic changes. Possible contributors include rising education levels, which made parents more aware of childrearing costs and raised the opportunity cost for educated women; rapid urbanization, which reduced the economic value of children as labor and made large families harder to sustain in crowded cities; and the rising cost of raising children, especially education, as families competed to secure better schooling in a more market-oriented economy. These dynamics suggest that even without strict quotas, many families were already inclined to have fewer children. The findings imply that simply lifting birth restrictions — as China did with the two-child policy in 2016 and the three-child policy in 2021 — may not be enough to reverse declining fertility, since underlying social and economic pressures continue to push family sizes downward.