Has Access to Government Data Given China’s AI Firms an Innovation Edge?

Has Access to Government Data Given China’s AI Firms an Innovation Edge? [ 3 min read ]

Insights

- Developing AI technology is data intensive. Access to government-collected data allows China’s facial recognition AI firms to innovate more in both government and commercial applications.

- Access to government data helped China’s firms become global leaders in commercial facial recognition technologies.

- Access to government-collected data could shape the development of AI across a variety of other important domains like healthcare, education, and basic science.

Source Publication: Martin Beraja, David Y. Yang, and Noam Yuchtman (2021). Data-intensive Innovation and the State: Evidence from AI Firms in China. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

China’s firms have emerged as global frontrunners in developing artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI) technologies. Developing AI technology is data intensive. By contracting with the state, China’s AI firms have access to government-collected data that surpasses in scale and scope data collected by private firms alone. Has this access to government-collected data given China’s AI firms an innovation edge? Using a newly constructed dataset of China’s facial recognition AI firms that contracted with public security agencies, researchers estimated the impact of access to government data on commercial AI innovation.

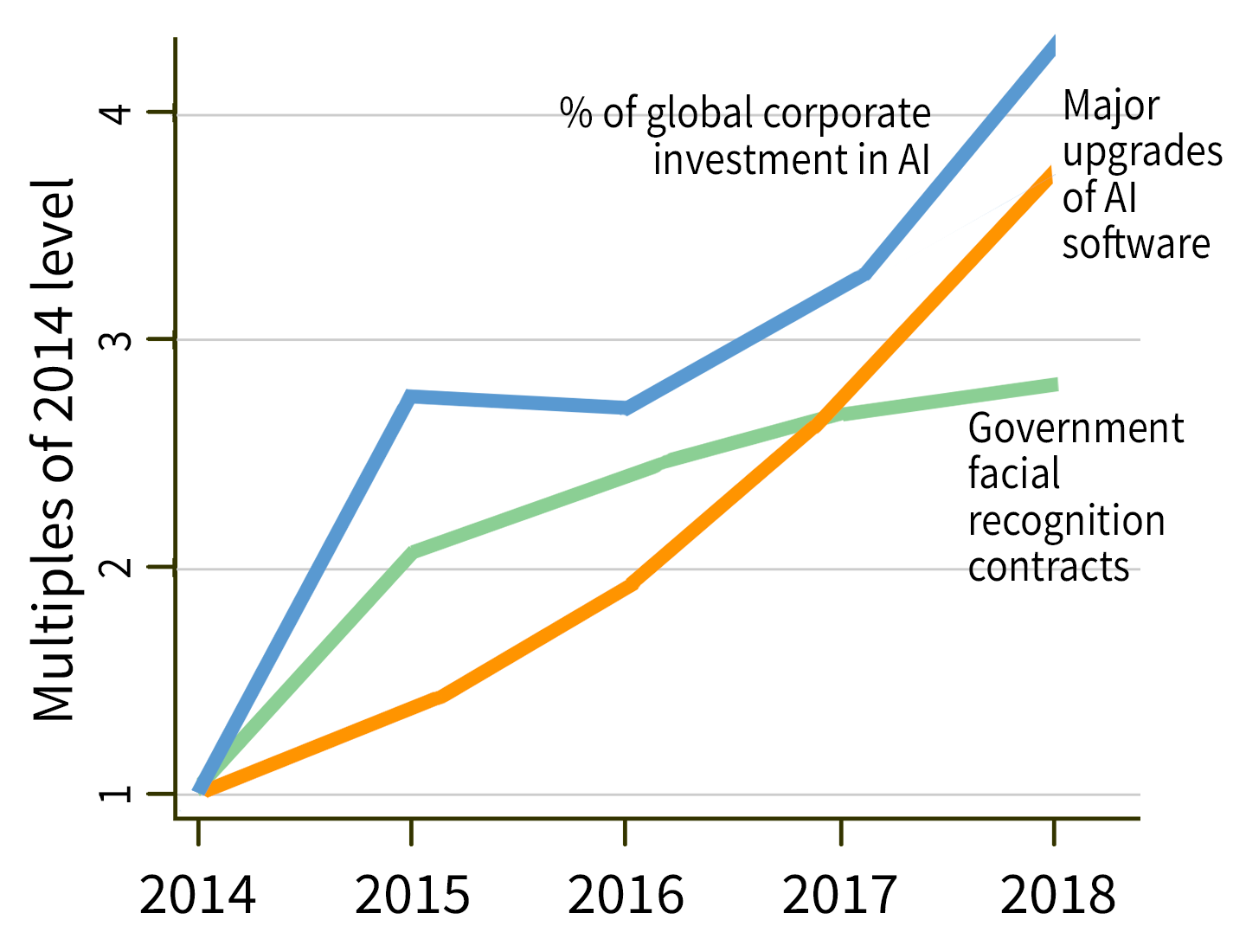

Measures of China’s AI development since 2014

The data. Researchers first identified virtually all of the nearly 8,000 facial recognition AI firms in China by using information from Tianyancha and Pitchbook databases. Of these, they identified 1,095 firms that had received at least one public security contract between 2013 and 2019 by connecting firm-level data with procurement contracts included in China’s Ministry of Finance’s Government Procurement Database.

Researchers then categorized each contract as either data-rich or data-scarce depending on the quantity of local high-resolution surveillance cameras that provided footage to the firm. This data could be used to train facial recognition AI algorithms to be accurate — valuable for both government and commercial applications.

Using software registration records from China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, researchers then compared the release rate and intended use (i.e., for commercial or government applications) of major software innovations by facial recognition AI firms that received either data-rich or data-scarce contracts.

More data produces more innovation. While both data-scarce and data-rich contracts positively affected firms’ software innovation, the receipt of data-rich contracts benefited firms to a larger degree. The researchers found that firms that received data-rich public security contracts generated 2.9 (51.9%) more government software products over a period of three years than firms that received data-scarce contracts. Furthermore, they found that access to government data also stimulated commercial software innovation. Firms that received data-rich public security contracts generated around 1.9 additional commercial software products over a period of three years after the contract, representing an increase in commercial software production of 20.2% relative to the pre-contract level.

Facial recognition AI software development resulting from government contracts

Innovation gains shareable across sectors. The increase in commercial software production took place despite firms needing to allocate their resources to increasing government software production as part of the contracts they receive. The evidence suggests that access to government data spills over to fuel AI innovation in both government and commercial sectors, overcoming the “crowding out” of resources that might occur when firms serve the state.

Government-collected data as innovation policy? These findings suggest that the provision of government data to China’s AI firms servicing the state contributed to their rise as global leaders in facial recognition technologies in the commercial realm. More generally, the findings highlighted here could apply to a range of other important domains where government data is predominant — geospatial and health data being two salient examples. This implies that states’ AI procurement and data provision can act as innovation policies that, intentionally or not, could shape the development of AI in certain sectors.