U.S.-China Economic Interdependence Has Shifted, Not Disappeared

U.S.-China Economic Interdependence Has Shifted, Not Disappeared [ 8 min read ]

INSIGHTS

- In 2020, less than 10% of U.S. production depended on global supply chains, yet about one-quarter to one-third of U.S. consumption — especially manufactured and high-tech goods — relied on global inputs, increasingly linked to China.

- By 2020, about 15% of China’s production depended on global supply chains, down from about 21% in the mid-2000s, while its dependence on foreign markets settled at 16–20%; of that foreign demand, the U.S. absorbed roughly 16–17%.

- Falling direct U.S.-China trade is often offset by rerouting through intermediaries such as Vietnam and Mexico, frequently via multinational firm links, highlighting the limits of bilateral trade restrictions.

- Both countries remain embedded in global supply chains. The U.S. is exposed primarily through consumption and China through production, and each relies on the other — directly and indirectly — for key inputs and final demand.

Read this brief on SUBSTACK

Progress on U.S.-China “decoupling” is often judged by trade data, with falling trade taken as evidence of weaker economic ties. But this view misses how modern supply chains operate. Many goods used in the U.S. are produced by foreign-owned firms operating domestically, which rely on global supplier networks that are not fully captured in bilateral trade statistics. A foreign-invested firm may still import key inputs from abroad through internal networks, even as measured trade declines. To reveal these hidden links, the researchers combine trade data with information on foreign investment and firm ownership, allowing them to assess the true extent — and limits — of U.S.-China decoupling.

The data. The paper combines detailed global production data with information on foreign-owned firms to show how countries are connected through modern supply chains. Using this approach, the authors examine global integration from several angles:

- Upstream dependence: How much production in the U.S. and China depends on foreign inputs

- Downstream dependence: How much of what the U.S. and China produces is ultimately sold to foreign buyers

- Consumption dependence: How much domestic consumption in the U.S. and China relies on value created outside these two countries, including foreign inputs embedded in final goods

The researchers also distinguish between U.S. and China dependencies on global supply chains that operate through direct trade — cross-border buying and selling (trade-related dependence) — and those that run through foreign investment, where multinational firms organize production across countries (FDI-related dependence).

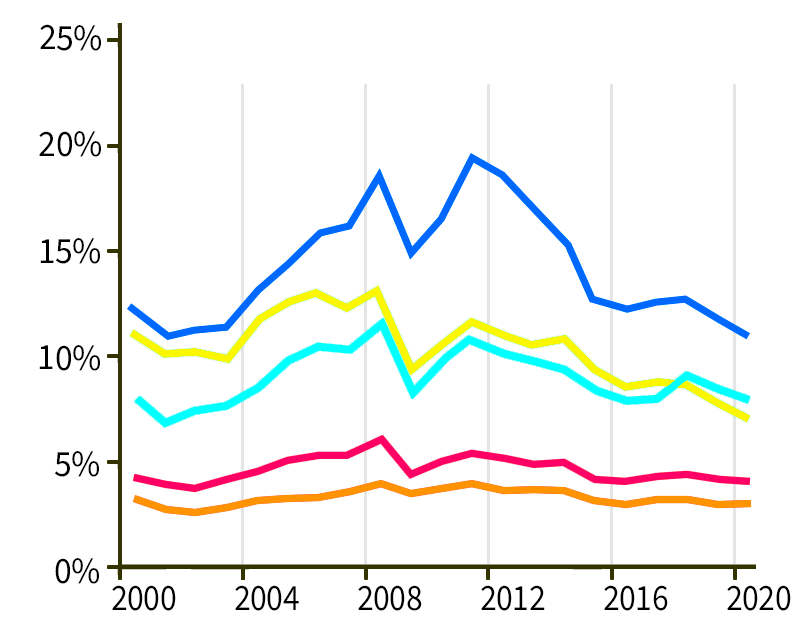

Dependence of U.S. production on foreign trade by industry

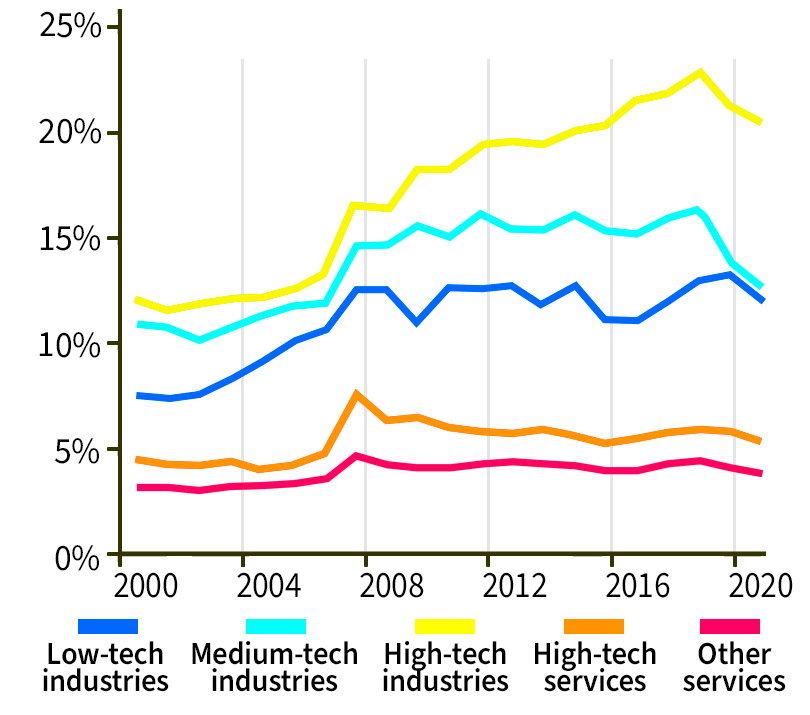

Dependence of U.S. production on foreign FDI by industry

U.S. production is largely domestic overall. Less than 10% of U.S. production is dependent on global supply chains, though exposure varies sharply by industry. Trade-based linkages appear in traditional manufacturing, where trade reliance peaked near 19% before the financial crisis and declined to about 11% by 2020, while services remain lightly exposed at below 5%. In contrast, FDI-related dependence centers on advanced manufacturing: upstream dependence in high- and medium-tech sectors such as electronics and pharmaceuticals peaked around 24%, and stabilized near 15%.

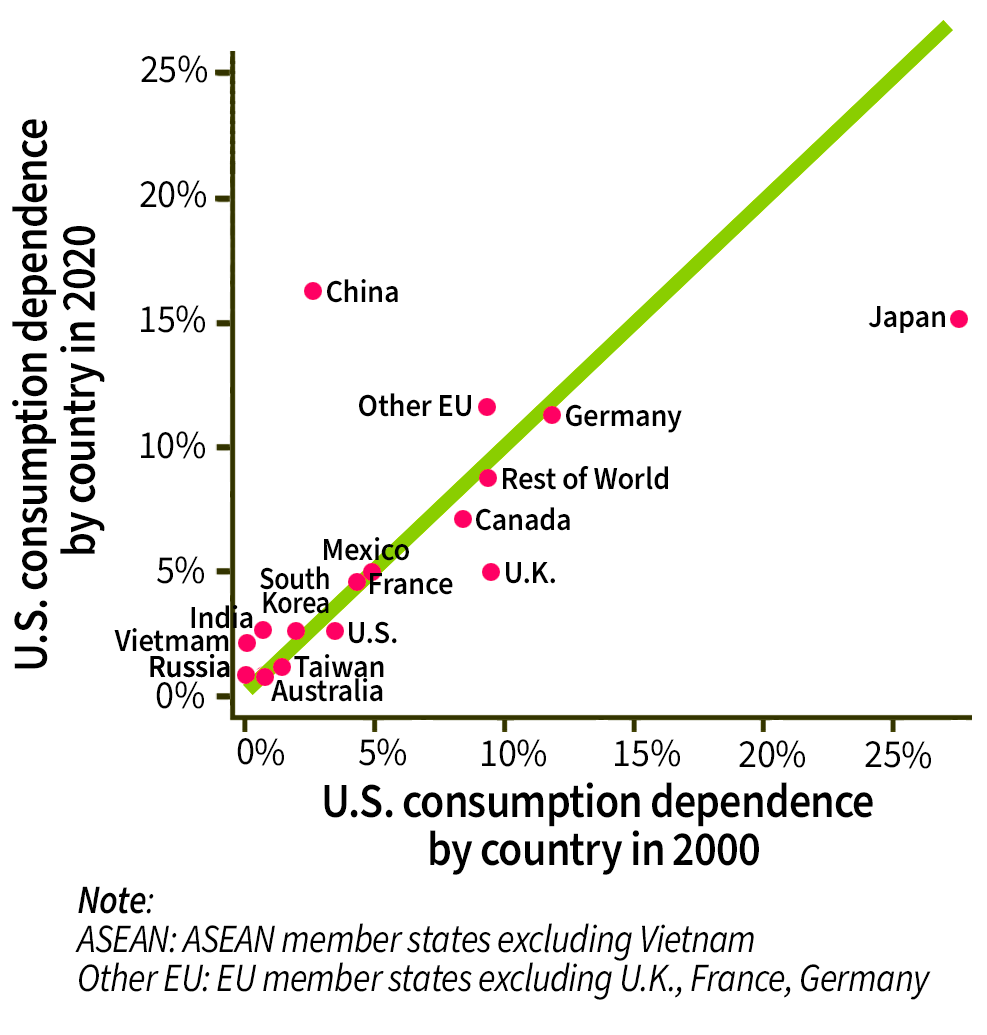

U.S. consumption is far more globally exposed than production, especially in manufactured and higher-technology goods. Roughly one-quarter to one-third of U.S. consumption relies on global supply chains. In traditional sectors such as textiles, trade-related consumption dependence rose sharply — from about 11% in 2000 to over 80% by 2020 — while high-tech products such as autos and electronics depend more on FDI networks. China’s share of value embedded in U.S. consumption dependence has grown from under 5% to over 15% overall, and much more in manufacturing, reaching nearly 44% in electronics and 56% in textiles.

Share of each country in U.S. consumption dependence in 2000 versus 2020

In contrast to the U.S., China remains more globally integrated on the production side and less so on the consumption side. By 2020, about 15% of China’s upstream production depended on global supply chains, while downstream dependence on foreign markets settled at 16–20 %, down from a peak of about 33% in 2006. Consumption dependence also declined over time, falling from a mid-2000s peak of roughly 23% to about 20% by 2020, reinforcing China’s role as a production- and export-oriented economy rather than a consumption-driven one. Across sectors, trade-based dependence has declined, while FDI-based dependence through multinational production networks has risen in advanced manufacturing, especially in automobiles and electronics. China has also diversified its supply chain exposure away from advanced economies toward ASEAN, emerging markets, and Rest of World.

China’s production system remains more globally exposed, particularly through export markets, even as overall supply chain dependence has declined. By 2020, 80% or more of China’s upstream production relied on domestic inputs, while about 15% depended on global supply chains. Downstream dependence on foreign markets peaked at about 33% in 2006 and settled at 16–20% by 2020, compared with upstream dependence, which peaked near 21% and declined to around 15%. Consumption dependence also moderated, settling at roughly 20% by 2020, reinforcing China’s role as an export-oriented production hub rather than a consumption-driven economy.

China’s upstream exposure persists in R&D-intensive manufacturing. Low R&D industries show relatively limited reliance on global supply chains, while medium-tech sectors remain trade dependent and high-tech manufacturing relies heavily on both trade and FDI channels. Across industries, trade-related upstream dependence has fallen, while FDI-related dependence has risen: in textiles, trade reliance declined from 16% in 2000 to 8% in 2020, while in automobiles, FDI-related upstream dependence increased from 10% to 16%. Similar increasing trends occurred in advanced electronics and machinery, reflecting the growing role of multinational production networks in more advanced manufacturing.

On the downstream side, China’s manufacturing remains highly export oriented. Trade-related downstream dependence exceeded 20% across manufacturing in the early 2000s and peaked before the global financial crisis at nearly 40% in low-tech manufacturing, before declining and stabilizing, with high-tech manufacturing remaining around 25–28% after 2008. Although smaller overall, FDI-related downstream dependence is concentrated in advanced manufacturing, rising to about 19–20% by 2017–2020, underscoring the growing role of multinational firms in China’s export structure.

China’s consumption dependence has increasingly shifted toward high-tech industries and toward FDI-based channels. Trade-related consumption dependence in high-tech industries rose above 30% in the mid-2000s before declining, while FDI-related consumption dependence increased steadily, reaching about 14% by 2020. In contrast, traditional products, such as textiles saw trade-related consumption dependence fall from 11% to 5%, while FDI-related consumption dependence rose sharply in automobiles, from 18% to 33%. At the same time, China’s supply chain geography has diversified away from the U.S. and Japan toward ASEAN, emerging markets, and the Rest of World, indicating rebalancing rather than retreat from globalization.

U.S.-China supply chain interdependence increasingly rerouted through third economies. From the U.S. side, indirect trade-related inputs from China embedded in U.S. production rose from under $5 billion in 2000 to over $30 billion by 2020, while FDI-related indirect sourcing remained below $15 billion. The effect is larger in consumption: China’s value embedded in U.S. consumption increased from under $20 billion to about $210 billion, raising China’s share of U.S. consumption-related global supply chain exposure from about 5% to roughly 15–16%. From China’s perspective, direct reliance on the U.S. market fell from nearly 20% to about 16–17%, even as indirect sales via intermediaries such as Mexico, Canada, Vietnam, and South Korea expanded sharply, with Mexico alone accounting for about one-quarter of China-linked inputs used in U.S. production — evidence of reconfiguration rather than true decoupling.

Falling bilateral trade is a poor proxy for economic decoupling. The analysis shows that the U.S. and China occupy distinct structural roles: China remains more exposed to global supply chains, especially through export markets, while U.S. production is more domestically embedded, while global exposures are concentrated in foreign-invested firms and consumption. Supply chains have become less geographically concentrated, with third countries absorbing shocks and limiting the scope for full decoupling. Overall, the evidence demonstrates that global supply chains — anchored in comparative advantage, economies of scale, and networked FDI — remain resilient to policy shocks targeting direct bilateral flows. Structural constraints limit the scope for full decoupling between major economies, as global production networks adapt by redistributing value through multilateral channels. For policymakers, this implies that strategies aimed at enhancing supply chain security must move beyond bilateral trade measures to account for the complex, multi-layered nature of supply chain dependencies.