How China’s College Boom Expanded Graduate Programs, Enrollment, and Employment for Americans

How China’s College Boom Expanded Graduate Programs, Enrollment, and Employment for Americans [ 5 min read ]

INSIGHTS

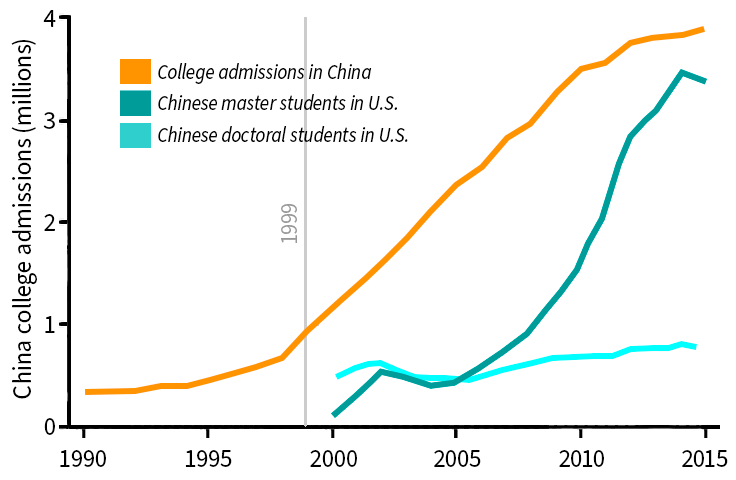

- Analysis of China and U.S. higher education data shows China’s college expansion — from 1 million annual students in 1998 to 9.6 million in 2020 — sparked a surge of graduates seeking advanced degrees in the U.S.

- Every 100 new college graduates in China produced about 3.6 Chinese graduate students in the U.S., explaining roughly 27% of the total growth in Chinese graduate enrollment in the U.S. since 2003.

- The rise was concentrated in STEM master’s programs at top U.S. public research universities.

- U.S. universities expanded programs rather than displacing students, and each additional Chinese master’s student corresponded to enrollment of +0.26 American and +0.50 international master’s students.

- In college towns, 100 more Chinese master’s students boosted net job creation by 0.7 percentage points, as their spending lifted demand for housing, dining, and services.

Read this brief on SUBSTACK

In 1999, China launched an ambitious higher education reform that transformed its college system by raising annual enrollment from just over 1 million students in 1998 to nearly 9.6 million by 2020. Designed to absorb surplus urban youth and build a knowledge-based economy, the reform created one of the fastest expansions of higher education in modern history. Yet its effects did not stop at China’s borders. Chinese graduate and undergraduate enrollment in U.S. universities grew nearly sixfold, from about 62,000 students in 2005 to more than 317,000 in 2019, with graduate students driving most of the increase. As millions of new Chinese graduates entered the global talent pipeline, U.S. universities saw a surge that reshaped graduate programs, campus finances, and even local economies. How did China’s domestic college expansion reshape American higher education?

The data. To trace how China’s 1999 college expansion affected U.S. higher education, the authors linked detailed administrative data from both countries. The authors combine China’s college admissions records — which detail how many students each province and major could enroll under the government’s quota system — with U.S. student visa data (SEVIS) showing where and what Chinese students studied in America. Because China’s central government set the quotas according to policy goals, some provinces and majors saw much larger increases in college admissions than others. Regions that were granted more college spots in certain majors produced more graduates in those majors, allowing the authors to see whether that surge led to more students pursuing related graduate study in the U.S. They then link these student flows to data on U.S. universities (Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, National Science Foundation) and local economies (U.S. Census Business Dynamics Statistics) to examine how rising Chinese enrollment shaped U.S. programs, finances, and college town job growth.

Policy-driven quotas create a surge of college grads seeking advanced study abroad. China’s higher education system operates under a centralized quota system, where the Ministry of Education decides how many students each province and major may admit each year. Because far more students take the national college entrance exam (Gaokao) than there are available seats, any quota increase for provinces or majors directly raises the number of students who can earn a bachelor’s degree. When Beijing expanded these quotas unevenly across provinces after 1999, some regions suddenly produced far more college graduates than others. With limited opportunities for high-quality graduate education at home, a growing share of these new graduates pursued advanced degrees in the U.S., creating measurable spillover effects for U.S. universities and local economies.

Chinese college grads seek STEM and master’s degrees in public U.S. research universities. Researchers find that for every additional 100 college graduates in China, about 3.6 pursued graduate study in the U.S. The effect was strongest for STEM majors and concentrated in master’s programs at top public research universities (e.g., the University of California, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin systems). The researchers estimate roughly 27% of the total growth in Chinese graduate enrollment in the U.S. between 2003 and 2015 can be attributed to China’s college expansion. Other important factors may be rising incomes in China, and variations in U.S. visa policies for international students.

Trends in China’s 4-year college admissions and admissions of Chinese graduate students by U.S. universities

Chinese demand boosts enrollment for U.S. and other international students. The analysis finds that each additional Chinese master’s student was associated with +0.26 American master’s students and +0.50 other international master’s students, indicating that U.S. universities grew their programs instead of displacing American or other international students. Small negative effects appeared only for international Ph.D. students (–0.09), perhaps reflecting crowding out at that level. The influx of Chinese students prompted U.S. universities to launch new master’s programs, particularly in STEM, adding roughly one new program for every 100 Chinese master’s students, with no rise in tuition. In other words, Chinese students helped expand university budgets and indirectly subsidized domestic students without driving up tuition per student.

Rise in Chinese graduate students lifted local employment. The study shows that the economic impact of Chinese students reached well beyond the classroom. Each additional 100 Chinese master’s students in a U.S. college town generated an increase of about 0.7 percentage points in net job creation, as their spending rippled through local U.S. economies. International students rent apartments, shop for furniture and groceries, eat at restaurants, and use local transportation and personal services. This steady demand for goods and services boosts employment in housing, retail, dining, and other service industries.

International spillovers of China’s college expansion. China’s domestic higher education policy inadvertently fueled the U.S. boom in STEM master’s programs, a key source of both talent and tuition revenue for American universities. China’s 1999 college expansion transformed Chinese higher education but also helped fund, fill, and sustain U.S. graduate programs — especially in STEM — while supporting local economies. As geopolitical tensions and tighter visa scrutiny threaten these flows, the study suggests the U.S. stands to lose not only students but also the spillover benefits they bring.