How China Collateralizes: Inside a $400 Billion Cash-Secured Lending System

How China Collateralizes: Inside a $400 Billion Cash-Secured Lending System [ 6 min read ]

INSIGHTS

- Analysis of two decades of China’s sovereign lending reveals nearly half of loans to developing country governments — 620 commitments worth $418 billion — are secured by specific revenue streams in the borrower country.

- About 79% of these collateralized loans are backed by cash in escrow or repayment accounts, mostly held in China’s banks, giving China’s lenders direct control of repayment flows.

- Over 60% of these secured loans draw on export revenues from commodities like oil, gas, copper, or cocoa, that are unrelated to the financed project.

- Roughly half of all secured loans share collateral pools or accounts that can span 15 to 20 years, tying borrowers to long-term repayment chains and limiting fiscal flexibility.

- This lending system may improve repayment discipline but reduces transparency and fiscal autonomy, complicating debt restructuring and multilateral oversight.

Source Publication: Anna Gelpern, Omar Haddad, Sebastian Horn, Paulina Kintzinger, Bradley C. Parks, and Christoph Trebesch (2025). How China Collateralizes. AidData working paper, William & Mary.

Read this brief on SUBSTACK

China’s post-2008 lending surge to emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) ranks among the largest global lending booms of the past 150 years. Many of these borrowers have weak legal and governance institutions, high debt risks, and limited access to international capital markets. How does China structure loans to maximize the likelihood of repayment?

The data. The study builds on AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance (GCDF) dataset, identifying all collateralized public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) loan commitments issued by Chinese lenders between 2000 and 2021. Using AidData’s Tracking Underreported Financial Flows (TUFF) methodology, the authors documented the collateral terms for each loan. The resulting How China Collateralizes (HCC) Dataset (Version 1.0) draws on more than 12,000 sources, including financial statements, loan and security agreements, IMF and World Bank debt analyses, official correspondence, and media reports — offering the most comprehensive global record of China’s secured sovereign lending to date.

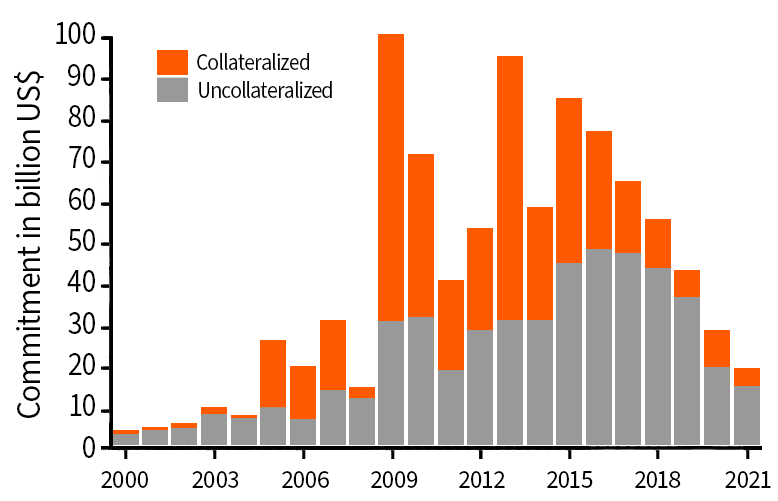

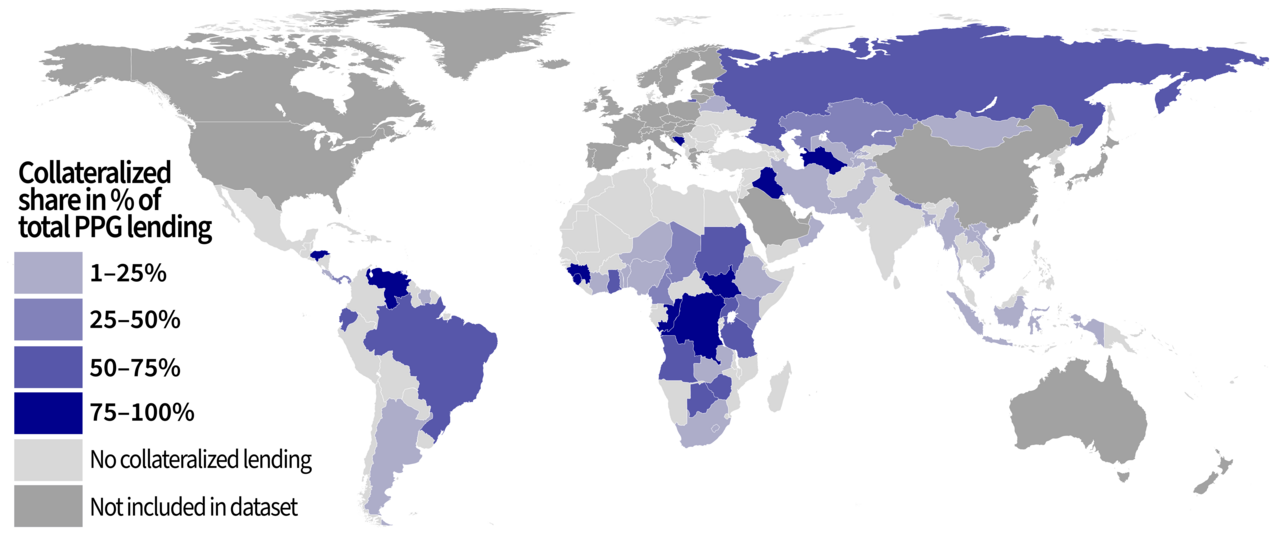

A global lending model built on collateral. Nearly half of all PPG loans that Chinese lenders extended to EMDEs between 2000 and 2021 are collateralized — that is, backed by a specific stream of revenue or asset that creditors can seize or control if the borrower defaults. PPG debt refers to obligations either directly owed by governments or guaranteed by them. The researchers identify 620 collateralized loan commitments worth $418 billion, extended by 31 Chinese creditors to 158 borrowers in 57 countries across Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. These loans represent nearly half of China’s total $911 billion PPG lending portfolio over the 22-year period, making collateralization and cash-flow control a defining feature of its sovereign lending model. The practice is led by China’s policy banks — chiefly the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank) — state-owned institutions tasked with advancing both national development and foreign-policy goals.

Cash, not assets, anchors repayment. Contrary to the common perception that China secures its overseas loans with ports, power plants, or other physical infrastructure, the vast majority of collateral is cash-based rather than asset-based. The researchers find that roughly four out of five (79%) collateralized loans are backed by foreign currency revenues deposited in dedicated escrow or repayment accounts, most of them held in China’s banks — often the same institutions that extended the loans. These arrangements allow China’s creditors to monitor, intercept, and control repayment flows directly, minimizing credit risk without requiring formal seizure of assets.

China's loans to developing country governments

Most loans are secured by export earnings unrelated to the financed project. The single largest source of collateral for China’s loans is commodity export revenue — not the income from the projects being financed. The researchers find that more than 60% of all collateralized loans are secured by foreign currency earnings from oil, gas, copper, cocoa, and other raw materials, typically deposited into escrow accounts controlled by China’s lenders. In many cases, these commodities have no direct connection to the financed project. For example, Angola’s oil exports were pledged to back loans for public infrastructure, while Ghana’s cocoa revenues secured unrelated power and road projects. By tying repayment to steady foreign-exchange inflows — rather than volatile project revenues — China’s lenders achieve greater repayment certainty while retaining flexibility to finance politically strategic or high-risk projects.

Cross-collateralization deepens dependence. China’s lenders often structure loans so that multiple debts share the same revenue stream or collateral pool — a practice known as cross-collateralization. Roughly half of all secured loans rely on shared repayment accounts or overlapping collateral arrangements, some spanning 15 to 20 years. In practice, a single export commodity or escrow account can secure several unrelated projects, sometimes financed by different lenders in China. This design effectively locks borrowers into long-term repayment chains, where funds tied to one loan cannot be redirected without creditor consent. To preserve access to new financing, borrowers must keep replenishing the same accounts, often at the expense of fiscal flexibility. For China’s state lenders, cross-collateralization enforces repayment discipline and reduces the risk of selective default. For borrowers, it creates a sticky and opaque dependence, complicating debt restructuring and making the financial relationship with China difficult to unwind.

China’s collaterized debt in emerging markets and developing economies

Control without publicity. The researchers find that China’s secured loans rely far more on “quasi-collateral” — that is, contractual and operational control over borrower revenues — than on formal, publicly registered property rights. In traditional sovereign or corporate finance, lenders might secure a loan through formal liens, pledges, or charges that are publicly recorded and legally enforceable. Chinese creditors, by contrast, prefer practical control: they use loan covenants, payment- routing agreements, and set-off rights that allow them to monitor and seize revenues directly as they flow through designated accounts. These instruments give Chinese banks the same functional protection as a lien — priority access to cash — without requiring registration or disclosure. In a lending environment where legal enforcement is uncertain and multiple creditors compete for repayment, this system offers speed, secrecy, and certainty. Debtors, too, may prefer such arrangements, which shield sensitive financial terms from domestic or international scrutiny.

Layered security, continuous control. China’s creditors often use multiple, overlapping security mechanisms — including escrow accounts, deposit covenants, offtake agreements, and quasi-collateral arrangements — applied from first disbursement to final repayment. Together, these tools give lenders priority access to borrower revenues at their source, whether from commodity sales, service fees, or foreign-exchange earnings, ensuring repayment flows remain uninterrupted. This “life-cycle layering” of security increases repayment certainty for high-risk borrowers and maximizes recovery prospects in case of default. Access to borrower revenues functions simultaneously as a source of repayment, information, and leverage, enabling Chinese creditors to safeguard their exposure and influence borrower behavior. The result is a lending model built for control and adaptability, blending commercial risk management with strategic statecraft.

Securing repayment at the expense of transparency, autonomy. Collateralization is a defining feature of China’s global lending model, enabling state-owned banks to adapt market tools — like escrow accounts and revenue routing — to make risky loans safer. But these same mechanisms carry trade-offs. Because restricted accounts are easily concealed, they can evade public scrutiny more effectively than liens on physical assets, undermining debt transparency. The structure also limits fiscal autonomy, as large shares of export or tax revenue are locked outside national budgets. By tying repayment to commodity or foreign-exchange inflows, the model heightens borrowers’ exposure to global price swings and erodes budgetary flexibility. For creditors and international institutions, the spread of undisclosed collateralized debt poses new challenges for sovereign debt management and restructuring.