The Consequences of Policy Centralization in China

The Consequences of Policy Centralization in China [ 6 min read ]

INSIGHTS

- Analysis of all 3.7 million publicly available policy documents from 2004 to 2020 shows the largely decentralized nature of policymaking in China.

- More than 80% of policies originate locally rather than from Beijing, driven by competition among local officials to win promotion through growth-oriented policy innovations.

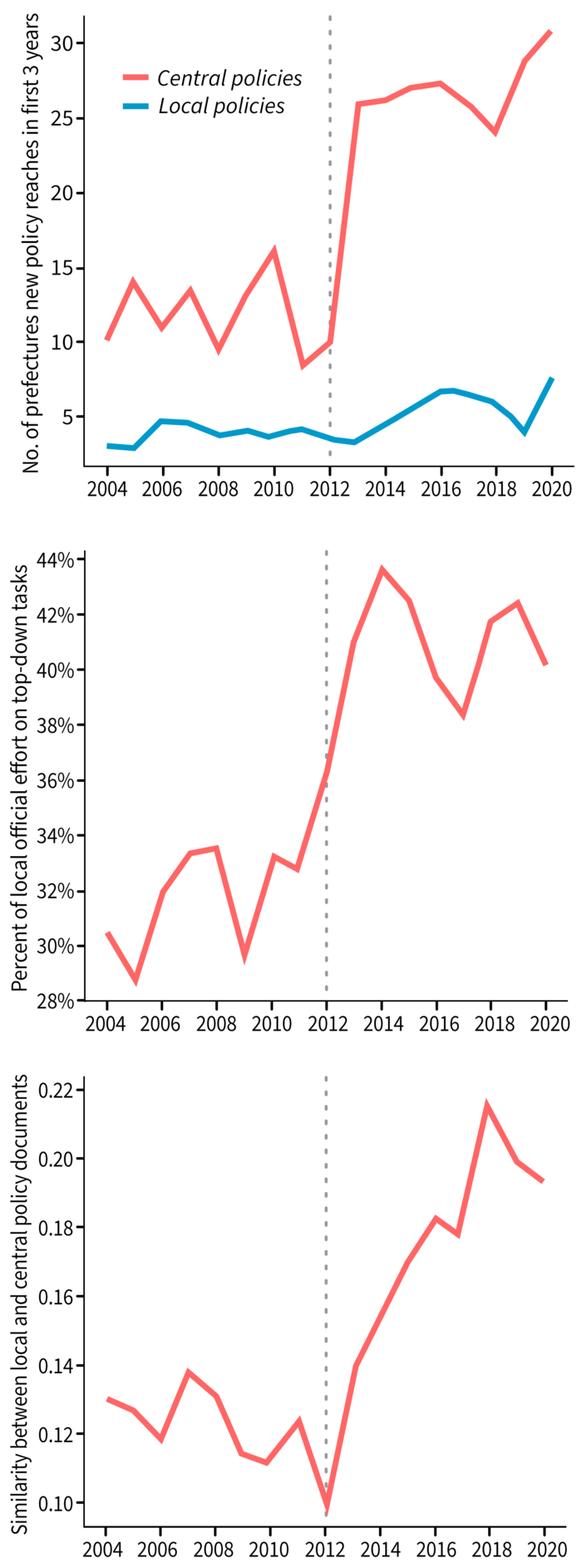

- However, after 2013, the share of central policies in local portfolios jumped by 40% from ~30% to over 40%, as promotions began rewarding compliance with Beijing rather than innovation.

- Analysis of all industrial policies in the sample shows that top-down industrial policies often fit local conditions poorly and are less effective, but they also reduce rivalry among local bureaucrats that can slow policy diffusion.

- Overall, the economic costs of policy centralization significantly outweigh its benefits.

- The analysis suggests China is trading growth and policy innovation for tighter control of the economy.

Read this brief on SUBSTACK

China’s rapid growth has long been characterized by local governments experimenting with new policies that later spread through the country, from the household responsibility system that decollectivized farming to free school lunch programs. Yet in recent years, Beijing has reasserted tighter control over local jurisdictions, raising the question: how much of local policymaking is driven by the center and does centralization in policymaking improve or undermine policy effectiveness?

The data. The researchers build a dataset of all published policies in China from 2004 to 2020 by combining 3.7 million policy documents from the legal database PKULaw and prefectural government work reports, using keyword analysis to identify 115,679 unique policies. Using text matching, they trace each policy’s “life cycle” — where it began, how it spread, and whether it was later adopted by Beijing. They then link policies to outcomes in output, exports, and patents, focusing on industrial policies to test how centralization shapes both local fit and policy effectiveness.

Most policymaking in China has been bottom-up, not top-down. From 2004 to 2020, China produced roughly 116,000 distinct policies — tech commercialization schemes, school lunch programs, water management protocols, and so forth. About 80% of these policies started at the local (prefectural) level rather than in Beijing. Of the locally initiated policies, 68% spread to an average of four other prefectures within three years, while 32% were never copied at all. Twenty-four percent of local initiatives eventually caught Beijing’s attention and were elevated to national pilots or directives. In any given year, about 63% of the policies in a locality’s portfolio were purely “bottom-up” — created or copied locally. And even when local governments adopted central directives, they often rewrote and tailored them rather than copying word for word. These patterns show that China’s policymaking has historically worked through local experimentation and adaptation rather than strict top-down control.

Local political incentives shape the spread of policies. By comparing similar leaders who stay in office versus those who leave, the authors show that local bureaucrats drive policy diffusion: once an official departs, the spread of their policies slows by about 40% and never recovers. This shows that leaders actively promote their policy innovations while in power because they get political credit for them. However, rivalry dampens this diffusion: cities led by competing bureaucrats (e.g., two prefectural Party secretaries with similar resumes aiming for a provincial-level job) are 1–2% less likely to copy each other’s policies, meaning over time perhaps hundreds of good policies never spread. A clear example is Beijing rejecting Shanghai’s successful license plate auctions in favor of its own lottery. In this way, local officials fuel diffusion, but career competition can block the spread of good ideas.

Policymaking more centralized since 2013. The analysis shows the share of top-down (central) policies in local portfolios rose from about 30% before 2013 to over 40% afterward — roughly a 40% increase. The local adoption rate of top-down initiatives has also nearly tripled: a typical central policy reached about 10 prefectures before 2013, but nearly 30 prefectures afterward. By contrast, the spread of bottom-up local policies stayed flat at around five prefectures within a three-year window. The likelihood that local governments exactly replicate (rather than adapt) central policy also doubled after 2013.

Centralization trends in policymaking

Compliance now rewarded over innovation. The rise in policy centralization coincides with a change in the incentive structure for bureaucrats. Before 2013, local officials who created or introduced bottom-up policies had about an 8% higher chance of promotion. After 2013, that link disappeared, and instead compliance became the key: complying faster and more completely to central directives raised promotion odds by about 8%. Similarly, the analysis shows that in policy areas covered by Central Leading Groups set up after 2013 to centralize decision-making, local experimentation slowed or reversed while compliance with central directives rose sharply. These findings suggest Beijing has reoriented bureaucratic incentives to reward compliance rather than experimentation and innovation.

Centralization comes with a steep economic cost. The authors weigh the costs and benefits of post-2013 centralization by examining how well policies match local conditions. They find top-down industrial policies are 18–22% less suited than bottom-up ones, measured by existing supply chains and prior private investment. For instance, central directives that pushed wind farms into provinces with poor wind resources left many to be “ghost farms.” They calculate that this suitability mismatch costs about ¥400 billion in lost industrial output, ¥32 billion in lost exports, and around 750 fewer patents each year. They find centralization has created savings by reducing frictions between bureaucratic rivals, but together the costs of centralization outweigh the benefits by more than four to one.

Top-down policies generally worse at picking winners. The researchers find central policies are no more likely than local ones to target industries with characteristics usually linked to high growth potential (like being large globally, fast-growing, or upstream in supply chains), and local governments often match or exceed the center in promoting high-growth sectors. Beijing does differ in prioritizing national security (e.g., industries targeted by U.S. export controls) and environmental goals, but overall centralization does not appear to make China better at picking economic winners.

Trading growth for control. The findings suggest that China’s policy process has long relied on local experimentation, but Xi-era centralization has tilted the balance toward compliance. While this may advance certain strategic goals, it also undermines local tailoring, making policies less effective and imposing large economic costs. The broader implication is that China may be trading away some of the growth and innovation benefits of decentralized governance to tighten political control.