FSI’s researchers assess health and medicine through the lenses of economics, nutrition and politics. They’re studying and influencing public health policies of local and national governments and the roles that corporations and nongovernmental organizations play in providing health care around the world. Scholars look at how governance affects citizens’ health, how children’s health care access affects the aging process and how to improve children’s health in Guatemala and rural China. They want to know what it will take for people to cook more safely and breathe more easily in developing countries.

FSI professors investigate how lifestyles affect health. What good does gardening do for older Americans? What are the benefits of eating organic food or growing genetically modified rice in China? They study cost-effectiveness by examining programs like those aimed at preventing the spread of tuberculosis in Russian prisons. Policies that impact obesity and undernutrition are examined; as are the public health implications of limiting salt in processed foods and the role of smoking among men who work in Chinese factories. FSI health research looks at sweeping domestic policies like the Affordable Care Act and the role of foreign aid in affecting the price of HIV drugs in Africa.

REAP’s Perfecting Parenting Project Shows Promise

A REAP project takes on the challenge of teaching parents in rural China that playing with their children is as important as feeding them.

Once every week for six months, a special team of family planning workers fanned out across the remote towns of Shaanxi Province or journeyed to isolated villages in the Qinling Mountains, the cradle of China’s civilization and habitat of the world’s remaining wild pandas. Determined to make a difference, the workers braved downpours in the dead of winter and long, treacherous roads to conduct weekly visits to families living in the region’s rural corners.

The little children who were their inspiration were often too shy to even make eye contact during the initial family sessions, but the government workers – part of a pilot group of parenting trainers – persevered. Eventually, the children welcomed the trainers with smiles, open arms and confident curiosity.

The parenting trainers brought toys to play with the toddlers, but not just for fun. The act of playing had a higher purpose.

Toddlers in rural China lag far behind their urban cohorts in developmental benchmarks, and Stanford’s Rural Education Action Program launched its Perfecting Parenting Project to tackle a key underlying cause: only a small fraction of rural parents interact with their young children.

“We want to get parents to improve their interactions with their toddlers,” said Alexis Medina, project manager of REAP’s health, nutrition and education initiatives.

That’s because the period between birth and age 3 is a critical developmental window, and interactive playing and verbal stimulation are important components of a child’s growth. REAP researchers know this, but a majority of parents in rural China do not.

For many parents or grandparents who are primary caregivers, the concept of actively engaging with their offspring is foreign. Research surveys revealed that less than 5 percent of parents in rural China regularly read to their babies and toddlers, and only 32 percent of them sing songs or use toys to play together. From their fieldwork, REAP researchers witnessed a pervasive view among parents: their young children are clothed and fed, isn’t that all they need?

In launching the 6-month pilot program in November 2014, researchers designed a week-by-week parenting curriculum – complete with books, balls and building blocks – to target key child development milestones.

“Before, the role of the family planning worker was to manage the quantity of the population,” said He Miao, one of the 70 parenting trainers recruited under the REAP project. “But from now on, our role is to improve the population’s quality.”

|

Little Cheng Junya transformed from shy and withdrawn to outgoing and engaged in just two months of parenting visits. |

As researchers work to gather project findings, REAP hopes Chinese officials will decide to expand the parenting training program.

Those at the frontlines are already convinced.

“My child never used to be so comfortable around strangers; I can’t believe she is now so outgoing,” the mother of little Cheng Junya remarked just two months into the program. “This is all because of the visits from such excellent teachers.”

Echoing his fellow parenting trainers, family planning worker Qin Yulu said, "In all the years I’ve been in this position, this is the most meaningful work I have ever done.”

REAP researcher Xueyang Liu summed up her view of the project’s success. “Each family planning worker manages different children and faces different challenges: sometimes the roads are difficult, sometimes the parents are unappreciative, and sometimes the children are unresponsive,” she said. But, she continued, “the parent trainers are united both by their willingness to overcome difficulty and by a passion for their work, and this has earned them the respect and love of the parents.”

For a closer view of the challenges and promise of the Perfecting Parenting Project, take a look at the following stories by REAP researchers who shadowed China’s first crew of parenting trainers.

|

Modern Parenting 101

REAP researcher Xinrui Gao joins parent trainer Liu Xianju on several weekly sessions during the six-month pilot program and describes here a caretaker’s dramatic shift in attitude toward modern parenting.

|

Little Activities Go A Long Way

REAP researcher Xi Zhiqi witnesses how the parenting program’s activities help to enhance a toddler’s verbal and social-emotional skills. This is her story of Little Wei.

|

A Mother’s Realization

REAP researcher Xueyang Liu describes here how a mother literally and metaphorically tramples on the project’s guidance materials before she comes to embrace the methods of active parenting.

These parenting trainers are propelled by thoughts of the children's recognition and trust when enduring tough travel conditions to reach their homes.

These parenting trainers are propelled by thoughts of the children's recognition and trust when enduring tough travel conditions to reach their homes.

|

Trainers: A Santa Qin and Honorary Godmother

The following two accounts by REAP researchers Wang Xiaohong and Jia Fang illustrate the immense dedication of two family planning workers from Shanyang County.

|

No Easy Road

REAP researcher Zhang Nianrui describes a-day-in-the-life of a pair of parenting trainers as she joins them on a rough journey to the remote village homes of the families under their charge for the pilot project.

Perfecting Parenting Pilot Launch Update

Baby Nutrition Qualitative Paper

Stanford researchers partner with local government to bring vision care to rural China

Hannah Myers

Students whose vision problems were corrected learned almost twice as much in a single academic year as myopic children who did not receive glasses.

Students whose vision problems were corrected learned almost twice as much in a single academic year as myopic children who did not receive glasses.

Having never had their vision tested, many rural children are unaware that they have poor vision, and that their eyesight is holding them back in school.

Teachers are generally a trusted source of advice in rural communities. When they buy in to vision care, families often do too.

|

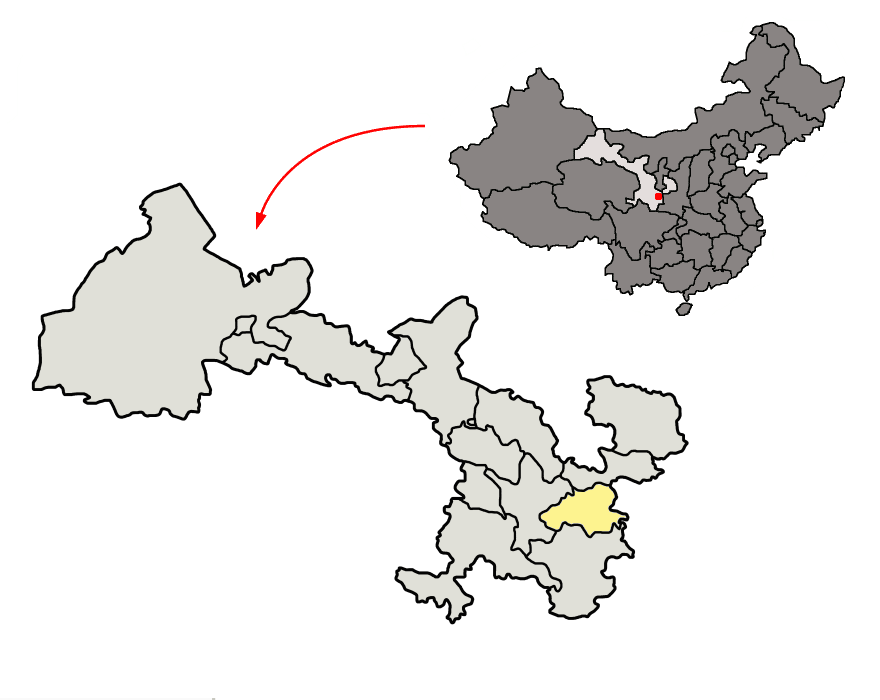

Yongshou, Shaanxi province (Photo Credit: Wikipedia) |

|

Qinan, Gansu province (Photo Credit: Wikipedia) |

A view inside Seeing is Learning's Yongshou vision clinic: newly certified refractionists and opticians diagnose and treat rural children.

Shaanxi Daily: China’s First “Parenting Trainers” Will Be Born in Shangluo

The Shaanxi Daily issued a press release on REAP's ongoing Perfecting Parenting project. This article was translated and reprinted with permission from The Shaanxi Daily. Read the original article (in Chinese) here.

China’s First “Parenting Trainers” Will Be Born in Shangluo

Commentary

In Shangluo, tucked away in the distant parts of the Qinling mountain range, 70 officials have already undertaken the assignment of “early child development parenting trainers.”

Yaojiang Shi, Director of the Center for Experimental Economics in Education at Shaanxi Normal University, was brimming with confidence as he received journalists, saying, “before long, they will pass the evaluations and become China’s first generation of parenting trainers.”

According to statistics, in 2013, 40 percent of 6- to 12-month-old children living in rural areas in Shaanxi province clearly lagged behind in cognitive ability and social-emotional development. Parents are only concerned that their children have enough to eat and warm clothes to wear, neglecting their mental health and development. Scientific research has proven that the first three years of a child’s life is a critical period for mental development. However, in China’s vast rural areas, there is still a blank space in place of education for 0- to 3-year-old children. In order to change this situation, China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission, Shaanxi Normal University, Stanford University in the United States, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences jointly established the “Perfecting Parenting” project. Following this project’s officially launch last November, 70 “parenting trainers” were recruited from among the family planning officials in 58 townships across Danfeng, Shangnan, Shanyang, and Zhenan counties, and 275 babies were randomly selected to take part in the project. After undergoing rigorous training, the “parenting trainers” will teach scientific child-rearing knowledge to children’s parents and caretakers through demonstration and guidance. By having parents interact more with their children through story telling, singing songs with them, playing games, and engaging in other parent-child activities, they aim to improve the babies’ cognitive abilities, motor development, and social-emotional development.

REAP and OneSight: Vision Care for 7,000 Kids in 8 Days

|

Contacts

Matthew Boswell: Project Manager, Seeing is Learning (boswell@stanford.edu)

Scott Rozelle: REAP Co-Director (rozelle@stanford.edu)

Gut Instincts: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices regarding Soil-Transmitted Helminths in Rural China

Soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) are parasitic intestinal worms that infect more than two out of every five schoolchildren in rural China, an alarmingly high prevalence given the low cost and wide availability of safe and effective deworming treatment. Understanding of local knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding STHs in rural China has until now, been sparse, although such information is critical for prevention and control initiatives. This study elucidates the structural and sociocultural factors that explain why deworming treatment is rarely sought for schoolchildren in poor villages of rural China with persistently high intestinal worm infection rates. In-depth, qualitative interviews were conducted in six rural villages in Guizhou Province; participants included schoolchildren, children’s parents and grandparents, and village doctors. We found evidence of three predominant reasons for high STH prevalence: lack of awareness and skepticism about STHs, local myths about STHs and deworming treatment, and poor quality of village health care. The findings have significant relevance for the development of an effective deworming program in China as well as improvement of the quality of health care at the village level.

The Prevalence of Anemia in Central and Eastern China: Evidence From the China Health and Nutrition Survey

Although China has experienced rapid economic growth over the past few decades, significant health and nutritional problems remain. Little work has been done to track basic diseases, such as iron-deficiency anemia, so the exact prevalence of these health problems is unknown. The goals of this study were to assess the prevalence of anemia in China and identify individual, household and community-based factors associated with anemia. We used data from the 2009 China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), including the measurement of he- moglobin levels among 7,261 individuals from 170 communities and 7 provinces in central and eastern China. The overall prevalence of anemia was 13.4% using the WHO’s blood hemoglobin thresholds (1968). This means in China’s more developed central and eastern regions up to 180 million people may be anemic. Some vulnerable subgroups were disproportionately affected by anemia. Seniors (aged 60 years and above) were more likely to be anemic than younger age cohorts, and females had higher anemia prevalence among all age groups except among children aged 7 to 14 years. We found a negative correlation between household wealth and the presence of anemia, suggesting anemia prevalence may decline as China’s economy grows. However, the prevalence of anemia was greater in migrant households, which should be experiencing an improved economic status.

Cuéllar looks back on leading FSI

For 14 years, Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar has been a tireless Stanford professor who has strengthened the fabric of university’s interdisciplinary nature. Joining the faculty at Stanford Law School in 2001, Cuéllar soon found a second home for himself at the Freeman Spogli for International Studies. He held various leadership roles throughout the institute for several years – including serving as co-director of the Center for International Security and Cooperation. He took the helm of FSI as the institute’s director in 2013, and oversaw a tremendous expansion of faculty, research activity and student engagement.

An expert in administrative law, criminal law, international law, and executive power and legislation, Cuéllar is now taking on a new role. He leaves Stanford this month to serve as justice of the California Supreme Court and will be succeeded at FSI by Michael McFaul on Jan. 5.

As the academic quarter comes to a close, Cuéllar took some time to discuss his achievements at FSI and the institute’s role on campus. And his 2014 Annual Letter and Report can be read here.

You’ve had an active 20 months as FSI’s director. But what do you feel are your major accomplishments?

We started with a superb faculty and made it even stronger. We hired six new faculty members in areas ranging from health and drug policy to nuclear security to governance. We also strengthened our capacity to generate rigorous research on key global issues, including nuclear security, global poverty, cybersecurity, and health policy. Second, we developed our focus on teaching and education. Our new International Policy Implementation Lab brings faculty and students together to work on applied projects, like reducing air pollution in Bangladesh, and improving opportunities for rural schoolchildren in China. We renewed FSI's focus on the Ford Dorsey Program in International Policy Studies, adding faculty and fellowships, and launched a new Stanford Global Student Fellows program to give Stanford students global experiences through research opportunities. Third, we bolstered FSI's core infrastructure to support research and education, by improving the Institute's financial position and moving forward with plans to enhance the Encina complex that houses FSI.

Finally, we forged strong partnerships with critical allies across campus. The Graduate School of Business is our partner on a campus-wide Global Development and Poverty Initiative supporting new research to mitigate global poverty. We've also worked with the Law School and the School of Engineering to help launch the new Stanford Cyber Initiative with $15 million in funding from the Hewlett Foundation. We are engaging more faculty with new health policy working groups launched with the School of Medicine and an international and comparative education venture with the Graduate School of Education.

Those partnerships speak very strongly to the interdisciplinary nature of Stanford and FSI. How do these relationships reflect FSI's goals?

The genius of Stanford has been its investment in interdisciplinary institutions. FSI is one of the largest. We should be judged not only by what we do within our four walls, but by what activity we catalyze and support across campus. With the business school, we've launched the initiative to support research on global poverty across the university. This is a part of the SEED initiative of the business school and it is very complementary to our priorities on researching and understanding global poverty and how to alleviate. It's brought together researchers from the business school, from FSI, from the medical school, and from the economics department.

Another example would be our health policy working groups with the School of Medicine. Here, we're leveraging FSI’s Center for Health Policy, which is a great joint venture and allows us to convene people who are interested in the implementation of healthcare reforms and compare the perspective and on why lifesaving interventions are not implemented in developing countries and how we can better manage biosecurity risks. These working groups are a forum for people to understand each other's research agendas, to collaborate on seeking funding and to engage students.

I could tell a similar story about our Mexico Initiative. We organize these groups so that they cut across generations of scholars so that they engage people who are experienced researchers but also new fellows, who are developing their own agenda for their careers. Sometimes it takes resources, sometimes it takes the engagement of people, but often what we've found at FSI is that by working together with some of our partners across the university, we have a more lasting impact.

Looking at a growing spectrum of global challenges, where would you like to see FSI increase its attention?

FSI's faculty, students, staff, and space represent a unique resource to engage Stanford in taking on challenges like global hunger, infectious disease, forced migration, and weak institutions. The key breakthrough for FSI has been growing from its roots in international relations, geopolitics, and security to focusing on shared global challenges, of which four are at the core of our work: security, governance, international development, and health.

These issues cross borders. They are not the concern of any one country.

Geopolitics remain important to the institute, and some critical and important work is going on at the Center for International Security and Cooperation to help us manage the threat of nuclear proliferation, for example. But even nuclear proliferation is an example of how the transnational issues cut across the international divide. Norms about law, the capacity of transnational criminal networks, smuggling rings, the use of information technology, cybersecurity threats – all of these factors can affect even a traditional geopolitical issue like nuclear proliferation.

So I can see a research and education agenda focused on evolving transnational pressures that will affect humanity in years to come. How a child fares when she is growing up in Africa will depend at least as much on these shared global challenges involving hunger and poverty, health, security, the role of information technology and humanity as they will on traditional relations between governments, for instance.

What are some concrete achievements that demonstrate how FSI has helped create an environment for policy decisions to be better understood and implemented?

We forged a productive collaboration with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees through a project on refugee settlements that convened architects, Stanford researchers, students and experienced humanitarian responders to improve the design of settlements that house refugees and are supposed to meet their human needs. That is now an ongoing effort at the UN Refugee Agency, which has also benefited from collaboration with us on data visualization and internship for Stanford students.

Our faculty and fellows continue the Institute's longstanding research to improve security and educate policymakers. We sometimes play a role in Track II diplomacy on sensitive issues involving global security – including in South Asia and Northeast Asia. Together with Hoover, We convened a first-ever cyber bootcamp to help legislative staff understand the Internet and its vulnerabilities. We have researchers who are in regular contact with policymakers working on understanding how governance failures can affect the world's ability to meet pressing health challenges, including infectious diseases, such as Ebola.

On issues of economic policy and development, our faculty convened a summit of Japanese prefectural officials work with the private sector to understand strategies to develop the Japanese economy.

And we continued educating the next generation of leaders on global issues through the Draper Hills summer fellows program and our honors programs in security and in democracy and the rule of law.

How do you see FSI’s role as one of Stanford’s independent laboratories?

It's important to recognize that FSI's growth comes at particularly interesting time in the history of higher education – where universities are under pressure, where the question of how best to advance human knowledge is a very hotly debated question, where universities are diverging from each other in some ways and where we all have to ask ourselves how best to be faithful to our mission but to innovate. And in that respect, FSI is a laboratory. It is an experimental venture that can help us to understand how a university like Stanford can organize itself to advance the mission of many units, that's the partnership point, but to do so in a somewhat different way with a deep engagement to practicality and to the current challenges facing the world without abandoning a similarly deep commitment to theory, empirical investigation, and rigorous scholarship.

What have you learned from your time at Stanford and as director of FSI that will inform and influence how you approach your role on the state’s highest court?

Universities play an essential role in human wellbeing because they help us advance knowledge and prepare leaders for a difficult world. To do this, universities need to be islands of integrity, they need to be engaged enough with the outside world to understand it but removed enough from it to keep to the special rules that are necessary to advance the university's mission.

Some of these challenges are also reflected in the role of courts. They also need to be islands of integrity in a tumultuous world, and they require fidelity to high standards to protect the rights of the public and to implement laws fairly and equally.

This takes constant vigilance, commitment to principle, and a practical understanding of how the world works. It takes a combination of humility and determination. It requires listening carefully, it requires being decisive and it requires understanding that when it's part of a journey that allows for discovery but also requires deep understanding of the past.