Smart Focus - Franchising a Sustainable Approach for School Eye Health in China

In the June 2016 publication of the EYElliance and World Economic Forum report, "Eyeglasses for Global Development: Bridging the Visual Divide," a case study for REAP's Smart Focus social enterprise was published on page 21. Read the entire report here.

The Rural Education Action Program (REAP), an impact-evaluation organization, aims to inform sound education, health and nutrition policy in China. Since 2011, REAP’s five randomized controlled trials have shown that quality vision care is the most cost-effective intervention for improving child welfare, and leads to large and sustainable increases in learning and school performance, along with positive spillovers to children who don’t have poor vision.

REAP is now establishing a network of for-profit vision centres based at county hospitals through an initiative called Smart Focus. Those centres partner with schools to deliver high-quality vision care. Optometrists administer six hours of training for classroom teachers, enabling the latter to conduct initial vision screenings and refer students needing more advanced care through a highly structured referral system. The teachers are provided free mobile-phone time as an incentive, and the vision centres earn revenue from urban consumers in a cross-subsidization scheme that supports providing care for poorer rural consumers whose unmet need is greatest. To date, REAP has provided access to free or affordable glasses for over 30,000 primary school students and screened an additional 120,000 children.

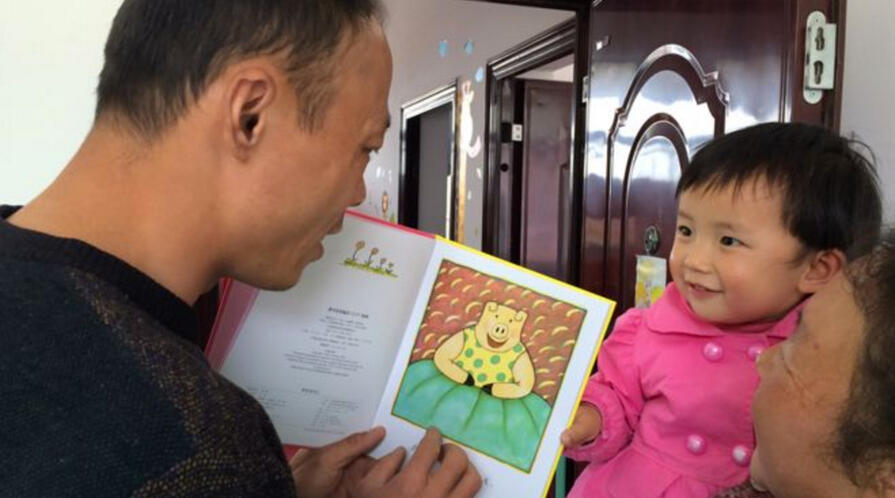

In addition to screening children and supervising their wearing glasses, teachers play a vital role in communicating with parents. Once a teacher’s screening indicates a child needs glasses, the teacher often spends significant time convincing parents that (a) the child’s condition requires attention, (b) the problem is correctable, and (c) taking the child to the vision centre to get glasses is highly advisable.

Vision centres dispense “first pair free” or very low-cost glasses to rural elementary- and middle-school students, while providing part of the urban market with refraction and eyewear on a fee-for-service basis. Giving away the first pair of glasses is not “just charity”; rather, it provides access to the huge untapped rural market. To build confidence, vision centres unconditionally guarantee the frames for three months and lenses for six months, something that no private optician does. (A noteworthy challenge arises, however, with parents who believe that low-cost or free services must also be of low quality; usage rates and eyeglass prices have been shown to rise in tandem.)