On the eve of the Lunar New Year, Beijing is bright and bustling. Keeping a promise made to a friend 2000 km away, a reporter walks along Zhongguancun Boulevard in search of a medicine called the "baota lozenge." However, more than twenty-some pharmacies of all sizes have all given the same answer: this once familiar anthelmintic drug has been off the counters of pharmacies for over 10 years!

In Sichuan and Guizhou, some 2000 km away, the final report from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Rural Policy Research Center and the Rural Education Action Project (REAP) on the current infection status of intestinal worms in children is fresh off the press. In the more than twenty years since the baota lozenge came off the market, prevention efforts against soil-borne worm infections in rural children have weakened and these parasitic infections traditionally affecting rural children have re-emerged!

According to results from a survey of 6 randomly selected nationally designated poor counties and 95 villages, in which 817 three to five year-old preschool-aged children and 890 eight to ten-year old school-aged children in Sichuan and Guizhou were screened for intestinal worms, REAP found that infection rates for intestinal worms (Ascaris, hookworm and whipworm) reached 22%: 21% for preschool-aged children and 23% for school-aged children.

In a country like China that has been experiencing an economic boom for the past 30 years, why do poor rural children today still have such a high infection rate of intestinal worms?

Delisting the baota lozenge and its effects on children's health

Among 817 three to five year-old preschool-aged children and 890 eight to ten-year old school-aged children randomly selected from 6 poor counties, the overall intestinal worm infection rate was high at 22%, mainly with Ascaris. Of the infected children, ~80% had roundworms, and 15% had multiple infections. This result overturns the presumption that intestinal worms infection decreases when standard of living increases.

A WHO report in 1999 explained that in tropical and subtropical regions, the loss from soil-borne parasitic diseases and schistosomiasis accounts for over 40% of the total disease burden. Those affected are mainly children; the diseases increase the risk of malnutrition, anemia, stunting, impaired cognition, and other diseases.

Actually, even before this report was published, China had already prioritized prevention of soil-borne parasitic diseases and schistosomiasis in public health measures. In the 50 years from the founding of new China to the early 1990s, the Chinese government had been devoted to increasing awareness of parasitic worm infections and systematic use of anti-parasite drugs as part of its prevention efforts to drastically reduce intestinal worm infection rates in children. However, in the last 20 years, not only have intestinal worms not been considered a priority in national infectious disease control, but the baota lozenge used consecutively for 10 years has also retreated from the market.

With the baota lozenge off the market and intestinal worm prevention at a low, what is the current health status of the vast number of rural children?

With this question in mind, CCAP and REAP's team, with the help of the Chinese CDC's Parasitic Diseases Control and Prevention Institute, conducted a field work investigation from April 2010 to June 2010 in Sichuan and Guizhou.

To ensure representativeness and the scientific nature of the survey, 6 nationally designated poor counties were randomly selected across the two provinces. After sampling areas were confirmed, the townships in each county were divided into 42 groups according to per capita net income and 12 townships were randomly selected from each group. Four sample townships were selected from each sample county. In every sample township, 2 sample schools were randomly selected; in every sample school, 2 sample villages served by the school were randomly selected; in each sample village, 11 eight to ten-year olds were selected for parasitic worm infection screening. At the same time, in every village, using child vaccination records (provided by township health center), the research team acquired the name list of all three to five-year old children in the two sample villages within that township. Eleven three to five-year old preschool-aged children were randomly selected from each sample village for screening for intestinal worms.

In this way, with collaborations with international parasitic worm expert consultants and recommendations from the Chinese CDC Parasitic Disease Control and Prevention Institute, 46 schools, 95 villages served by the schools, and a total of 1707 children were randomly selected to form the sample. Of these, 817 were three to five years old and considered preschool-aged and 890 were eight to ten years old and considered school-aged.

The investigation and screening of children for parasitic worms consisted of three main parts: anthropomorphic measures, basic socioeconomic information and children's fecal samples. A team of nurses from Xi'an Jiaotong University was responsible for measuring children's height and weight; REAP team members collected information on sample children's age, gender, parental education levels, hygiene and family characteristics, as well as whether children had received anthelmintics in the past year and a half. Chinese CDC Parasitic Disease Control and Prevention Institute analyzed fecal samples.

Over the course of a few months of data analysis, results indicate: sample areas have high infection rates of intestinal worms, but discrepancies exist across different age groups, areas and types of parasitic worm infection. Twenty-one percent of preschool-aged and 23% of school-aged children in sample areas were infected with Ascaris, hookworm or whipworm or a combination thereof. Infection rates meet WHO's criteria for mass treatment. In one province, 34% of preschool-aged and 40% of school-aged children have one or more of the three types of worms. In the other province, although infection rates are lower among preschool and school-aged children, they are still 10% and 7%, respectively. Among the types of worm infection, Ascaris is most severe, with infection rates reaching 17%, followed by whipworm (7%), pinworm (5%), and hookworm (4%).

At the same time, regional differences are quite distinct. In one of the provinces, 7 villages out of 48 sample villages and 2 schools out of the 23 sample schools had prevalence rates above 20%. About half of the sample villages and schools suggest evidence of parasitic worm infection. In the other province, one quarter of the sample villages and one third of the sample schools had infection rates above 50%. Evidently, intestinal worms prevention is an important public health concern that needs to be emphasized by local disease control centers.

Besides high infection rates of parasitic worms, the intensity of infection should not be ignored. Among preschool-aged children in the two sample areas, each gram of fecal matter contains 23,568 and 17,064 roundworm eggs, respectively. According to WHO standards, this level of roundworm infection is considered a "moderate" infection level. Hookworm and whipworm infection intensities are lower; only hookworm infection among school-aged children in Sichuan reached "moderate intensity," while other infection levels could be considered "low intensity".

What causes parasitic worm infection in these children?

The investigation shows that infection in preschool-aged children correlates with maternal education and family health conditions, while infection in school-aged children correlates with school health education and hygiene conditions. Of particular importance is that even though eliminating worms costs only 4 RMB per person per year, prevention efforts have not been included in local medical services in less accessible rural areas with high infection rates.

In the third grade class of Longshan elementary school in Machang township, Pingba county, Anshun city, Guizhou province, one question continues to haunt head teacher Li: "Why does our class have students calling in sick and missing school every day?"

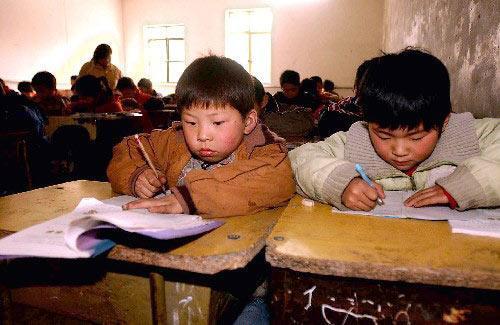

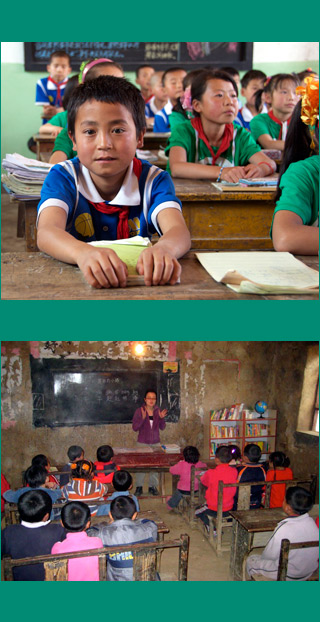

On the surface, Teacher Li's third grade class is no different from schools in other rural areas in China. The students are typical rural schoolchildren filled with curiosity, who have bright eyes, dirty hands, and colorful backpacks.

However, if you pay close attention, you will notice they are very different from same-aged children in other areas. These students are mostly on the small side, and look one to two years younger than their actual age. At recess, there is none of the typical pent-up energy kids usually have after sitting in a classroom all morning. No excited children chasing one another, no shouts from the hubbub of play, no lively rhythm of skipping rope. It is as if a blanket of weariness has descended on these children.

The culprit is no other than intestinal worms. According to the introduction provided by researchers Drs. Xiaobing Wang and Chengfang Liu, Longshan elementary school has one of the highest infection rates of all sampled schools, reaching 70%. One of the two sample villages covered by Longshan elementary schools had parasitic worm infection rates as high as 80%.

What effect does parasitic worm infection have on children's growth and development? REAP's results indicate that worms lead to anemia in 22.7% of the rural school-aged children, and delayed physical development in 30%, which is a 400% higher risk than non-infected children. Compared with non-infected children, affected children have below-average weights, shorter stature, weaker body constitution, and general underdevelopment, just to name a few characteristics.

The project research team, Chinese CDC Parasitic Disease Control and Prevention Institute's Guofei Wang and Xibei University's Professor Yaojiang Shi believe that worms not only cause discomfort and nausea, but also lead to significant learning (memory) and cognitive impairments.

Renfu Luo, an assistant researcher at CCAP, believes that the underlying reason is that high infection rates have long been neglected, and so have caused low school attendance rates and limited attention spans, which ultimately lead to infected children falling behind their healthy counterparts.

In fact, according to the WHO's parasitic worms prevention guidelines, for schools like Longshan elementary school that are rural and inaccessible, two mass administrations of albendazole or mebendazole (both available on the market) are needed per year. However, the reality is, even though the medicine costs only 4 RMB per person per year for kids from Longshan elementary school and other nearby rural villages, the public health infrastructure required to combat the disease has not been incorporated into the scope of medical services.

If the Longshan elementary school sample is an example of the typical conditions in western villages, what are the implications on a larger scale? CCAP researcher Linxiu Zhang believes that in the long run, if parasitic worm infections in children continue to be neglected in national infectious disease control, the future efficiency and productivity of the rural labor force will be affected. From an education perspective, and in light of an increasingly competitive skill-based socioeconomic environment, intestinal worms may very well be the primary driver for perpetuating the vicious intergenerational cycle of poverty.

From the 6 sample counties investigated over the course of 3 months, the researchers were able to see with their own eyes the health situation of Longshan elementary school and other sample schools. The researchers could not resist asking, how did these kids become infected with intestinal worms? Living in more or less the same environment, why do some kids become infected while others escape that fate?

After repeated comparison and analysis of the data, researchers found that these poor rural village children's infection rates are correlated with mother's education level, children's unsanitary hygiene habits (such as not washing hands before meals and after bathroom use), and family health conditions (such as access to potable, clean water, toilet sanitation, and livestock/poultry breeding habits). At the same time, children's habit of wearing split pants for convenient urination/defecation also exacerbates the risk for worm infection. Because mothers are usually responsible for their children's eating and health habits at home, mothers with lower education levels often lack knowledge about health and nutrition improvement and intestinal worm disease severity. Thus, the higher the mother's education level, the lower the child's chance of infection. Interestingly though, father's education level has no visible effect on the child's risk of infection.

For school-aged children, the main reason for intestinal worm infection is that poor rural village schools lack safe drinking water services and facilities. In these sample schools, researchers found that the schools' water quality is a far cry from the national standards for safe, potable water. However, because these schools cannot provide boiled water, many students have no choice but to drink unprocessed, unboiled water.

Drinking unboiled water is a main cause for infection in children. According to calculations made by the research team, consuming unboiled water increases infection by 11%, while washing hands before meals can decrease infection by about 4.6%.

Poor school sanitation conditions are also a main driver for infection. Research findings indicate that two-thirds of the sampled schools did not have sinks for washing hands; even though a few schools have constructed sinks, because there is no running water or soap, they are really just for display. Also, none of the sampled school treated their bathroom waste using appropriate and safe chemical methods, which not only affects sanitation in and around the school, but also facilitates parasitic worm cross-infection.

Insufficient knowledge or poor public health measures?

Prevention of intestinal worm infection for poor, rural village children is unstructured, unsystematic, and combined with school sanitation and health education deficiencies, has triggered high infection rates in remote rural areas. However, the primary reason for this phenomenon is the lack of basic public health measures in rural settings.

The analysis of the data begs the following question: Why, in the midst of rapid economic progress, are there still elevated levels of infection among children in certain regions? We know from China's past successes in infectious disease control that basic public health services are all that is needed to effectively prevent parasitic worm infection. And cheap, effective, safe, and reliable anthelmintics are easily acquirable. Yet high levels of infection persist. Why?

As early as 1960, many international experts in global development praised China for its ability, despite its developing status and low average income, to effectively provide public health services for rural citizens and children. Turning back to that page in long forgotten history, China was actually able to prevent parasitic worm disease at impressive proportions in a short span of 50 years. The success can be attributed to strong adherence to prevention and the hard work of medical and public health personnel.

Data indicate that in the 1970s, the parasitic worm infection rate among China's children reached about 80%. The 1990 seminal nation-wide human parasites survey found that overall parasitic prevalence remained high at 63%, with the intestinal worm infection rate at 59%. Even though China's population infected with Ascaris, whipworm and hookworm at that time reached 140 million people, due to administration of anthelmintics in rural villages combined with health education and waste management as part of a concerted prevention effort, the parasitic infection rate ultimately plummeted at the beginning of this century. Soil-borne worm infection rates decreased to about 20%.

This was an accomplishment during a time of massive prevention and treatment by the infectious disease control unit. This period marked a golden era for public health measures in rural villages. Almost everyone over 35 years of age born in rural areas can still vividly remember the many "barefoot" and village doctors who performed regular check-ups for various villages, treated common diseases for free, and educated people about basic disease prevention and health practices. One of the most commonly seen services was providing free "baota" lozenges or albendazole to children, in the form of a pink or blue, mildly sweet anthelmintic pill.

However, this "free lunch" period did not last long. After conducting field work studies on the sample villages, researchers discovered that entering into the 1980s, with decreasing investment in rural public health and medical services, the rural health system sustained by "barefoot" doctors crumbled, and villagers have since rarely enjoyed basic public health protection. With severe financial shortages and lack of coordination, education and public health collaboration efforts also descended into stagnation. School-aged children's health surveillance and vaccination measures reached a nearly historic low. In recent years, the Chinese government has begun to redirect attention to rural public health. However, the prolonged 20-year disappearance of basic rural public health services from the national radar has initiated the revival of many once eliminated diseases in these areas. Some villages actually exist in zones of concentrated outbreaks.

With an impressive record of success just twenty years ago, why is the prevention of parasitic worms in children still so difficult in an economically blossoming and increasingly health conscious society? Is it due to insufficient monetary funding, gaps in knowledge, or some other reason?

Researchers believe that even with the disappearance of the high quality and inexpensive "baota" lozenge, other drug treatments for parasitic worm infections in children exist today, requiring just two administrations per year and a low cost of less than 4 RMB. However, the critical problem is that health and education administration in various areas currently lack substantive, effective coordination in their anthelmintic efforts. Small investments that maximize benefit to many people's livelihoods are slow to be made.

According to field interviews, when the "baota" lozenge retreated from center stage, local health and education departments debated about who should take responsibility for children's health, and teachers and principals also shunned the problem. In discussions with some teachers from sampled schools, researchers found that teachers scratched their heads over poor parental care in addressing the issue. Despite all schools establishing relevant health education curricula, due to limited manpower and financial resources, most schools do not have full-time health education teachers and do not distribute unified teaching materials to students, so the curriculum can hardly be implemented.

Actually though, cross-department cooperation has occurred in the past. At the end of the last century, the Ministries of Health and Education used to collaborate on formulating and implementing effective anthelmintic interventions for children through stratified school-based efforts that provided anthelmintics for free to children in severe infection areas. At that time, treatment of parasitic worms in children was highly successful.

However, the reality is that in the sampled areas, a relatively large portion of medical institutions lack funding support and the necessary facilities. Thus, they have no capacity to freely provide parasitic worm prevention services to children, resulting in 55% of sampled rural children being infected with intestinal worms. These children have never been administered any anthelmintics, and even for those who have been treated, they did not undergo any examination of the distribution of intestinal worm infection beforehand. Parents often solely look for changes to their children's appetite or compare their children's weight with that of other same-aged peers. They rarely seek medical help or follow a doctor's advice, and many freely allow their kids to take the medications on their own. Due to limited knowledge about parasitic worm infections and prevention, parents never followed-up to make sure the medication worked and are unclear about reinfection risks. The vast majority of parents wrongly assume that using anthelmintics just once will prevent infection in the long run.

By investigating children who have used anthelmintics in the past 18 months (47% of the sample), researchers found that even after treatment, intestinal worms reinfection rates in children remained at a high 20%. In one sampled province, intestinal worms reinfection rates in children were at a startling 33% after treatment. These results indicate that across sampled areas, one-third of preventive medication efforts produced no effect. What is needed is integration into rural public health services system with long-term follow-up, surveillance, and medical intervention when appropriate.

An indisputable reality is that the worm burden reduction is different from other types of infectious disease control because specialized equipment and knowledge are needed for detection of intestinal worm infection in children, and the disease often strikes poor, remote rural areas. Thus, even though rural public health services have received more attention today, it remains difficult to attract the focus of relevant departments.

Recommendations from experts in multiple fields: Increase the level of parasitic worm prevention and improve health facilities in poor rural schools

The situation of intestinal worm infection is one parameter by which to measure the economic development and social civilization level of a country. However, some poor areas in China today still have high rates of infection, which is inconsistent with the rapid socioeconomic development in the country, sounding a loud warning bell for the Ministries of Health and Education.

International research indicates that for every 1 RMB spent on health education, 6 RMB is saved in medical treatment fees. For the reemergence of intestinal worms affecting children in some rural areas, are there other better solutions?

Renfu Luo, an assistant researcher at CCAP, suggests that the pressing matter at the moment is to mobilize parasitic worms prevention efforts in poor rural areas, renew inclusion of such efforts in the government's infectious disease control focus, develop and implement a long-term health education curriculum in schools that covers parasitic worm prevention, as well as launch health promotion campaigns in rural communities. With this foundation, the government needs to organize relevant experts to go deep into the vast number of poverty-stricken villages. Talks, newspapers, bulletins, and slogans, among other methods that address intestinal worms prevention; disseminating information on individual and public health; motivating schools, children, and families; urging poor rural communities to change unsanitary habits and thereby eliminate or reduce external factors affecting health are among the basic interventions that can lower the infection rates in impoverished children.

Yaojiang Shi, Director of the Xibei (Northwest) Research Center for Economic and Social Development and Professor of Xibei University, believes that the education administrative departments must intensify improvements to public health and drinking water facilities in poor rural schools while simultaneously nurturing and teaching children about good health habits. On the supply side, schools should provide students with safe drinking water and improve toilets and hand-washing areas; these improvements in external conditions can facilitate decreases in parasitic worm infection rates.

CCAP deputy director Linxiu Zhang recommends that the central government should augment investment efforts to manage environmental sanitation in poor rural villages, improve water source environmental protection and water quality, promote context-specific domestic pollution control, strengthen livestock pollution measures, reduce livestock waste, recycle, and process waste through non-hazardous treatment. At the same time, the government should consider including parasitic worm prevention services in the Rural Cooperative Medical System in poverty-stricken areas, allowing children to truly enjoy the benefits of national public health services for intestinal worms detection and treatment, experience effective decreases in infection rates, and develop healthily to reach their potential. (Article correspondent: Jin Ke)

Relevant background information

The past and present of the "baota" lozenge

"Baota" lozenge targets a common type of parasitic worm, the intestinal roundworm. At the beginning of the liberation period, roundworm infection was prevalent throughout China's cities and countryside.

As part of the former Soviet Union's aid projects in China, China imported wormseed seeds to test plant from the Soviet Union. The 20 g of seeds (can imagine the value of the seeds) imported were divided into 4 portions and under the protection of public security personnel, were transported to 4 state-owned farms in cities given the task of test planting: Hohhot, Datong, Xian and Weifang. Only one trial in Weifang announced success. In order to keep the information secret, Weifang publicized the successful test plant as "Pyrethrum No. 1" to the outside.

This roundworm-specific anthelmintic is derived from wormseed in the Chenopodiaceae family of herbs. It was initially administered in pure tablet form, but in order to expedite administration to children, a certain proportion of sugar was added, and the medicine was transformed into a light yellow and pink cone-shaped pill that resembled a pagoda ("baota"). People thus named this medication the "baota" lozenge.

The anthelmintic encountered many hardships including the Great Leap Forward, which through mistaken industrial techniques led to 3500 kg of raw materials going to waste. Then, the rebels from the "Ten Years of Turmoil" took the promising manufacturing of wormseed medication and left it in a terrible mess. In 1979, the Ministry of Health and State Food and Drug Administration promoted universal administration of "baota" lozenge. But in September 1982, all dosage forms and raw materials were eliminated. By the early 1990s, "baota" lozenge had disappeared from China.

The dangers of a few important types of intestinal worms

Intestinal worms mainly infect children, and due to competition with the host for nutrients, often lead to malnutrition and anemia in infected children, compromised physical and cognitive development, and even death from complications.

Ascaris larvae migration can lead to larvae-induced pneumonia and allergic reactions, while adult roundworms residing in the small intestine can destroy gastrointestinal function, generating abdominal pain, loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea or constipation and even severe complications such as intestinal obstruction, biliary duct ascariasis, and appendicitis.

Hookworm resides in the duodenum and small intestine, sucking up nutrients and blood in children, leading to anemia, poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, pale nails and facial complexion, dizziness, feebleness, shortness of breath, palpitation etc. Chronic infection can affect children's growth and development and severe infection can cause anemia-induced congestive heart failure.

Whipworm resides in children's cecum and appendix and consumes tissue fluid and blood for sustenance. Infected individuals can experience appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, bloody stool and other symptoms.

Pinworm's unique feature is that it stimulates itchy sensations in the anus and genitals at night, affecting sleep with associated symptoms of poor appetite, emaciation, irritability, night terror etc and can induce ectopic complications such as appendicitis.

“Growth and development starts with agriculture,” said Rozelle. “Agriculture provides the basis for sound, sustained economic growth needed to build housing, invest in education for kids, start self-employed enterprises, and finance moves off the farm.”

“Growth and development starts with agriculture,” said Rozelle. “Agriculture provides the basis for sound, sustained economic growth needed to build housing, invest in education for kids, start self-employed enterprises, and finance moves off the farm.” The government provided more indirect market support by publicly investing in better roads, communications, and surface water irrigation. Groundwater was left to the private sector. There were no water or pumping fees nor subsidies for electricity, keeping it completely deregulated. As a result, 50 percent of cultivated land in China is irrigated, compared to 10 percent in the US and only four percent in sub-Saharan Africa.

The government provided more indirect market support by publicly investing in better roads, communications, and surface water irrigation. Groundwater was left to the private sector. There were no water or pumping fees nor subsidies for electricity, keeping it completely deregulated. As a result, 50 percent of cultivated land in China is irrigated, compared to 10 percent in the US and only four percent in sub-Saharan Africa. Adding fuel to the fire, investment in rural health, nutrition, and education remains far from sufficient. Only 40 percent of the rural poor go to high school resulting in 200 million people who can barely read or write.

Adding fuel to the fire, investment in rural health, nutrition, and education remains far from sufficient. Only 40 percent of the rural poor go to high school resulting in 200 million people who can barely read or write.