|

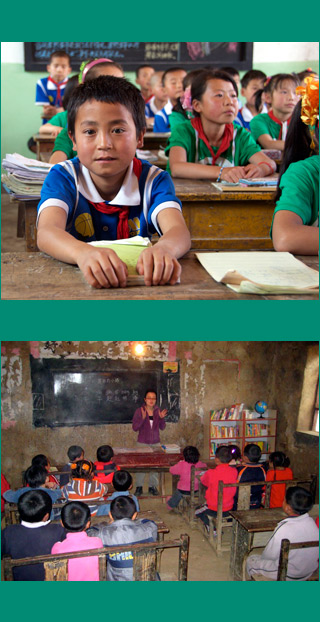

| Poor education mortgaging the future? Students in a Gansu province school, where many are anemic (top); another class room in Loess Plateau. (Top Photo: Adam Gorlick) |

DINGXI PREFECTURE: Wang Hongli, 8 years old, lives in a remote rural village on the Loess Plateau in one of China’s poorest and most agricultural provinces, Gansu. His prospects for living the good life are as bleak as the landscape. He is not on track to become part of China’s emerging middle class, the free-spending, computer-savvy, person-of-the-world often featured in the western media.

Hongli is a pseudonym. His parents work in a faraway industrial zone, coming home for only three weeks at Chinese New Year. His grandmother takes care of him and his siblings on the weekends, and during the week he lives in a dorm, three to a bed with 36 other students in an unheated room 4 by 4 meters.

Hongli suffers from iron-deficient anemia, but neither his family nor his teacher knows he is sick. Even if his anemia is discovered and treated by the researchers who have documented 30 percent anemia among children in poor rural areas, it likely will recur after he finishes the study, with furnished dietary supplements. Despite educational pamphlets, he’ll likely revert to a diet of staple grains and bits of pickled vegetables.

Unsurprisingly, Hongli’s grades are not good. In China’s competitive school system, he has only a slight chance of attending high school, much less college. In China’s future high-wage economy, all Hongli can hope for is a menial job in the provincial capital, Lanzhou, or as a temporary migrant elsewhere. Without urban permanent residency, hukou, he will have limited access to urban social services. He may suffer chronic unemployment, or resort to the gray economy or crime. He also may never marry – one of the millions of “forced bachelors” created by China’s large gender imbalance.

|

In China’s future high-wage economy, |

Hongli is not alone. In fact, he’s one of 50 million school-age youth in China’s vast poor rural hinterlands. Recent studies by Stanford and Chinese collaborators show that 39 percent of fourth-grade students in Shaanxi Province are anemic, with similarly high rates elsewhere in the northwest; up to 40 percent of rural children in the poor southwest regions, e.g., Guizhou, are infected with intestinal worms. Millions of poor rural students throughout China are nearsighted, but do not wear glasses.

Because China’s urbanites have fewer children, poor rural kids like Hongli represent almost a third of China’s school-aged children, a large share of the future labor force. These young people must be healthy, educated and productive if China is to have any chance of increasing labor productivity to offset the shrinking size of its aging workforce.

Many observers presume that China’s growth will continue unabated, drawing upon a vast reservoir of rural labor to staff manufacturing plants for the world. In fact, to a considerable extent, China’s rural areas have already been emptied out, leaving many villages with only the old and the very young. The growth of wages for unskilled workers exceeds GDP growth.

Better pay should be good news for poverty alleviation. However, rising wages push up the opportunity cost of staying in school – especially since high school fees, even at rural public schools, are among the highest in the world.

It’s myopic to allow rural students to drop out of junior high and high school – mitigating the current labor shortage, but mortgaging their futures. Recent studies demonstrate that eliminating high school tuition – or reducing the financial burden on poor households – improves junior high achievement and significantly increases continuation on to high school. Yet unlike many other developing countries, China does not use incentives to keep children in school, such as conditional cash transfers. The public health and educational bureaucracies also do not proactively cooperate to remedy nutritional and medical problems – including mental health – that school-based interventions could address cost effectively.

|

Less than half of youth in China’s poor rural areas go to academic high school; less than 10 percent head to college. |

The educational system, based on rote memory and drill, doesn’t teach children how to learn. The vocational education system is ineffective. Instead, China’s schools tend to focus resources on elite students. Tracking starts early, and test scores are often the sole criterion for success. A recent comparative study documents that China’s digital divide, with lower access to computers in poor rural areas, is among the widest in the world.

China’s government is increasing expenditures for school facilities and raising teacher salaries. However, these steps are far from adequate. During South Korea’s high growth, almost all Korean students finished high school. Today, less than half of youth in China’s poor rural areas go to academic high school, and the percent going to college remains in the single digits.

Greater investment in public health and education for the young people in China’s poor rural areas is urgent. If the government waits 10 years, it may be too late to avert risks for China’s stability and sustained economic growth.

Surely China could easily address this problem? A third of Chinese were illiterate in the early 1960s; now, fewer than 5 percent are. By 2010, about 120 million Chinese had completed a college degree. Chinese also enjoy a relatively long life expectancy compared to India and many other developing countries, and basic health insurance coverage is almost universal.

But the pace of change and citizens’ expectations are higher as well. Most Chinese assume that basic nutritional problems and intestinal worms were eradicated in the Mao era. China’s mortality halved in the 1950s; fertility halved in the 1970s. As a result, China will get old before it gets rich. Population aging, rapid urbanization and a large gender imbalance represent intertwined demographic challenges to social and economic governance. The policy options are complicated, the constraints significant, the risks of missteps real and ever-present.

|

China’s prosperity depends on youth mastering skills to thrive in a technology-driven world. |

Timely policy response is complicated by competition for resources – pensions, long-term care, medical care for the elderly and more – as well as significant governance challenges arising from a countryside drained of young people. The well-intentioned programs for what government regards a “harmonious society” create large unfunded mandates for local authorities. Attempts to relocate rural residents to new, denser communities provoke anger at being uprooted and skepticism that local authorities simply want to expropriate land for development.

Millions of migrant workers – like Wang Hongli’s parents – return to their rural homes during economic downturns. Urbanization weakens this capacity to absorb future economic fluctuations. Government efforts at “social management” – strengthening regulatory control of informal social groups and strategies for diffusing social tensions – expand the bureaucratic state, a central target of popular discontent.

Premier Wen Jiabao’s announcement of a 7.5 percent growth target – the lowest in two decades – has been expected. Future economic growth will moderate partly because of demographics, but mostly because productivity gains slow as an economy runs out of surplus rural labor and converges on the technological frontier. Costly upgrading of industrial structure will squeeze the government’s ability to deliver on its promise of a better future for all, stoking social tensions.

China’s stability and prosperity, and that of the region and the globe, depends on how well today’s youth master the knowledge and skills that enable them to thrive in the technology-driven globalized world of the mid-21st century. Resilient public and private sector leaders of the future must be able to think creatively. Therefore, China’s government should respond to population aging by acting now to invest more in the health and education of youth, especially the rural poor.

FSI researchers consider international development from a variety of angles. They analyze ideas such as how public action and good governance are cornerstones of economic prosperity in Mexico and how investments in high school education will improve China’s economy.

FSI researchers consider international development from a variety of angles. They analyze ideas such as how public action and good governance are cornerstones of economic prosperity in Mexico and how investments in high school education will improve China’s economy.

"It is increasingly important for our students to understand what it means to be citizens of the world, to bring a more international perspective, to be able to communicate with others from different backgrounds or with different expertise," Stanford President John Hennessy said at the opening of SCPKU.

"It is increasingly important for our students to understand what it means to be citizens of the world, to bring a more international perspective, to be able to communicate with others from different backgrounds or with different expertise," Stanford President John Hennessy said at the opening of SCPKU.

The SCPKU opening drew hundreds of academics, donors and government officials.

The SCPKU opening drew hundreds of academics, donors and government officials.