Huffington Post: How Glasses Can Help Solve Rural China's Schooling Problem

Matt Sheehan

China Correspondent, The WorldPost

October 12th, 2015

Simply giving nearsighted children glasses can dramatically boost their school performance. Convincing teachers and parents is harder.

This article is the second in a What’s Working series that looks at innovative policy solutions pioneered by the Rural Education Action Program. REAP brings together researchers from Stanford University and China to devise new ways to improve rural education and alleviate poverty. You can read the first article in the series here.

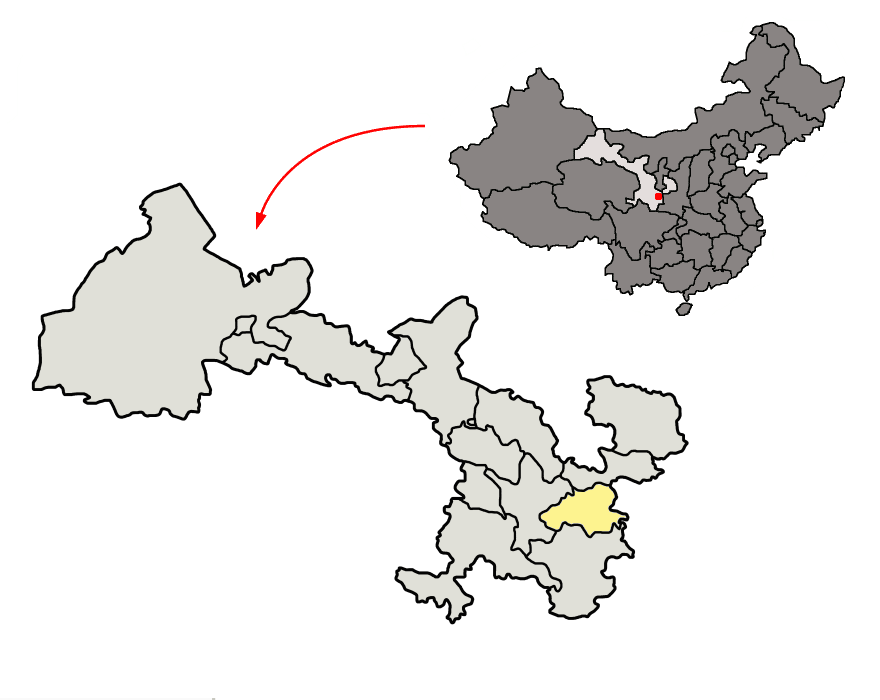

QIN'AN COUNTY, China -- Wei Wentai can barely be heard over the crescendo of cackles coming from the hallway. Fourth graders everywhere cane be boisterousness, but today the presence of two foreigners, an exotic breed in the rugged hills of western China, has driven these kids into a frenzy.

You could try to reason with the children: tell them they need to quiet down because Dr. Wei is here to train their teachers in how to perform vision tests. Those tests will give some kids free glasses so they can see the blackboard, dramatically improving their grades and chances of graduating high school.

But yeah, that’d be about as effective here in rural Gansu, in China's northwest, as it would be in Alabama, and it takes the lunch bell to drag the mob away from the classroom window.

With relative peace restored, Wei continues to tutor the 12 village schoolteachers in the basics of eyesight and education. Having grown up nearby, he knows what superstitions to dispel (“No, glasses do not make your eyes worse”) and what points to drive home (“Yes, glasses dramatically improve grades for nearsighted students”). Despite receiving his medical training in Shanghai, Wei returned home after graduating and always speaks in the local dialect when training the teachers to perform this basic eye exam and write referrals.

Teachers in Weng Yao village practice administering eye exams. Photo credit: Matt Sheehan

It’s a simple presentation tailored to this county, but one predicated on years of trust building and scientific trials by researchers on both sides of the Pacific Ocean.

Driving the project, called Seeing is Learning, are researchers from Stanford University’s Rural Education Action Plan (REAP) and Shaanxi Normal University’s Center for Experimental Economics in Education (CEEE). These groups operate in an emerging field of development economics that prizes rigorous experimentation over theory. Concrete interventions, randomized controlled trials and impact analysis are what drive their research and policy recommendations. Randomized controlled trials compare a randomly assigned group of participants receiving a particular treatment being studied with one not receiving the treatments. These trials are often called the gold standard of scientific research.

REAP and CEEE have spent almost five years accruing the political capital and research results that they hope will overcome one of the biggest obstacles standing between rural Chinese kids and a high school diploma: most of them can’t even see the writing on the blackboard.

Like many of their peers around East Asia, rural Chinese children suffer high rates of myopia. Around 57 percent are nearsighted by middle school, according to one REAP study. Unlike schoolchildren in Singapore or in China’s cities, most kids growing up in the Chinese countryside are ignorant of and isolated from vision care.

Students line up for a vision screening organized by REAP and CEEE.

In hundreds of visits to rural Chinese classrooms, REAP program director Matt Boswell has rarely seen a bespectacled face. A patchy and inadequate rural medical system, the high cost of glasses and cultural preferences for eye exercises over glasses (what one researcher calls “voodoo health”) mean that most children growing up in townships and villages never take a vision test.

“There is no eye care at the township level in China,” said Boswell. “Period.”

That void has a huge impact on education. In a study published in the British Medical Journal, REAP and Chinese researchers showed that giving myopic kids free glasses improved their math test scores by about as much as reducing class sizes. Those improvements came despite the fact that only 41 percent of students who were prescribed glasses actually wore them regularly. According to Boswell, when results were limited to the students who actually wore the glasses they were given, the impact proved enormous: it roughly halved the achievement gap between these rural students and their urban peers in just nine months.

A girl tries on her first pair of glasses at the Qi'nan County Hospital. Photo credit: Matt Sheehan

Improvements of that size represent some of the juiciest low-hanging fruit in Chinese education. Sixty percent of children in the countryside will drop out before high school, many due to failed grades and entrance exams. These tens of millions of dropouts threaten to throw a wrench in the Chinese government's plan to transition to a service- and innovation-based economy.

But when dealing with China’s bureaucracies, having a simple solution to a vexing problem isn’t enough to start harvesting that low-hanging fruit. The real art and science of the project came in aligning bureaucratic interests to get it off the ground.

“Every issue has its own little ecosystem,” Boswell said.

For Seeing is Learning, that ecosystem involved education officials committed to the eye exercise regime, schools that closely guard access to their students, families who are deeply suspicious of the effect of eyeglasses and hospitals that saw no reason to screen rural kids.

Students hurry to lunch at a school in Weng Yao village. Photo credit: Matt Sheehan

To break the impasse, the researchers had to first get local education bureaucrats on board. Randomized controlled trials proved the effectiveness of glasses and debunked the myth of eye exercises. They caught the eye of a powerful official in the nearby city of Tianshui, whose backing opened the doors to local schools. With REAP’s pledge to subsidize glasses, the hospitals suddenly saw large new markets materialize.

As a kicker, one trial found that when teachers were offered an iPad if their students were wearing glasses during random inspections, usage rates jumped from 9 to 80 percent.

“Hospitals love it because they get in the schools. Principals love it because of the impact on scores,” said Boswell. “We love it because the kids are learning.”

Turning that newfound excitement into a working program required the creation of two “Model Vision Counties” in which nurses and doctors like Wei Wentai receive accelerated optometry training. In order to expand that reach from the county seat down to the village, REAP ran another trial to see if teachers could conduct accurate eye exams after just a half-day training (answer: yes). So the newly trained doctors now rotate through the village schools, training teachers who then refer students to the hospital vision centers for proper prescriptions.

An elementary school teacher practices administering an eye exam during training. Photo credit: Matt Sheehan

Now the researchers are looking to scale up the program to six counties and at the same time turn the vision centers into sustainable social enterprises. Using their privileged access to schools, the vision centers can sell glasses to urban children with the resources to pay. Those profits then subsidize the first pair of glasses for rural kids, and repay REAP's initial loan, which REAP can then reinvest in creating further Model Vision Counties.

It’s a new model for REAP and one that prompts many new research questions. Can the vision centers earn enough revenue to both subsidize glasses and keep the hospitals happy? Will teachers enforce wearing eyeglasses if given a simple mandate rather than an iPad? Will the impact of the first pair of glasses convince rural parents to purchase the second pair?

Those questions will be investigated and answered when the project scales up. But as this van winds its way back down from the village to the county hospital, Wei Wentai reflects on the work they’ve done.

A child takes an eye exam administered by REAP and CEEE.

These parenting trainers are propelled by thoughts of the children's recognition and trust when enduring tough travel conditions to reach their homes.

These parenting trainers are propelled by thoughts of the children's recognition and trust when enduring tough travel conditions to reach their homes.

Students whose vision problems were corrected learned almost twice as much in a single academic year as myopic children who did not receive glasses.

Students whose vision problems were corrected learned almost twice as much in a single academic year as myopic children who did not receive glasses.