"Our Parents Are All Gone": Understanding the Impacts of Migration on a Generation of Chinese Children

"Our Parents Are All Gone": Understanding the Impacts of Migration on a Generation of Chinese Children

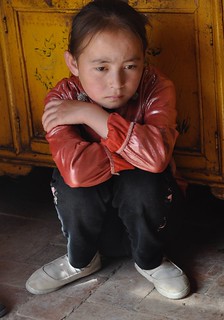

Imagine a childhood where, if you were lucky, you only saw your parents for a few days over the holidays every year. This is reality for 1 in 5 children in China. Left-behind children (LBCs) remain in rural villages while their parents migrate to cities for work. Although research has found that all children in China’s rural areas are more vulnerable than their urban counterparts, LBCs may be even more likely to suffer from a number of developmental setbacks. In addition, stories of abuse and suicide among LBCs are regularly reported in the media.

Due to the fast-paced industrialization and growth of China’s cities, an increasing number of rural Chinese working-age individuals have flooded urban centers in hopes of finding higher-wage jobs than those in their rural hometowns. However, as working-age individuals move to cities, they often leave behind their children and elderly parents in the countryside. This is because access to public and social services (such as schools, medical care, and pensions) are tied to an individual’s legal place of residence (their hukou) in China. This means that if children follow their parents to cities, they will likely be unable to attend school or access state medical care. For this reason, many parents believe that it is better for their child to be left in the countryside with a surrogate caregiver.

Consequently, the number of LBCs in China has increased over the last decade and was estimated to exceed 60 million children in 2010. To put this number in perspective, there are in total about 74 million children in the United States. Clearly, the well-being and human-capital development of LBCs will have important implications for China’s future if the number of urban migrant workers continues to increase and LBCs themselves begin to enter the workforce. Therefore, additional research is needed that is focused on determining the impact that being “left-behind” has on lifelong outcomes given (1) the competing forces of increased disposable income and parental absence and (2) different “types” of LBCs.

|

As a result of increased efficiency in agricultural production, few employment opportunities remain in China’s rural areas. For many working-age individuals the only opportunities for wage-earning employment exist in cities many miles away from their place of birth. Although this means that parents often must live away from their children, it also means that they have increased disposable income that can help them provide for their children’s health and education. This “income effect” often manifests itself in positive effects on educational outcomes. However, the income effect is often off-set to a certain degree by the effect of decreased parental care. When parents migrate for work, children are often left with surrogate caregivers or begin boarding at school. Many LBCs are left with grandparents, who are often illiterate and incapable of adequately providing for all of the child’s needs. Those students who board at school while their parents work far from home also face a unique set of issues due to the fact that they likely lack any sort of caregiver-figure. The effect of decreased parental care can be seen in deteriorated mental health and self-esteem and increased social anxiety among LBCs.

Recent research has also suggested that the trade-off between increased income and decreased care may be influenced to a large degree by who in the household migrates. LBCs are a relatively heterogeneous group, as any child that has at least one parent migrate for work is considered a LBC. However, due to differences in household composition, it may not be clear how the type of household migration will affect child outcomes. For example, when a child’s father migrates and mother remains at home, LBCs may benefit compared to their peers if their father can earn higher wages and their mother still cares for them. In contrast, if both of a child’s parents migrate for work and they are left in the care of their grandmother, who is unable to help them with school work or adequately provide for them, they may face worse outcomes than other rural children. Disentangling how the nature of household migration affects the outcomes of LBCs will be important in understanding and devising policy solutions that are sensitive to the needs of this multifaceted group of children.

In response to the need to better understand this complex group of children, REAP has been conducting research on the state of LBCs and the impact that being “left-behind” has on children’s developmental, educational, and mental health outcomes. Over the past decade, REAP studies have collected a large amount of quantitative data on household migration and children’s educational, mental health, and life skill outcomes. Findings from these data suggest that, on average, LBCs do not fare worse than other rural children in terms of health, nutrition, and education. However, when LBCs are broken down according to the nature of household migration, certain types of LBCs have been found to fare worse than others in terms of educational outcomes and mental health outcomes.

The Purpose of This Summer Project:

Although we have a large amount quantitative data that can be leveraged to study the condition of China’s LBCs, to date little effort has been made to study this issue from a qualitative perspective. This summer, we will attempt to add a human aspect to the REAP’s previous research and understand the mechanisms through which being left-behind affects children by conducting interviews with LBCs.

While we are in China, we will first devise qualitative interview questions and an interviewing protocol. Then, we will head to the rural countryside to conduct interviews with left-behind children, with the goal of writing an academic paper that describes the situation of LBCs and explains how being left-behind can affect the future outcomes of these children. After the end of our field work we will transcribe, translate, and analyze our qualitative interviews. We will then synthesize our qualitative findings with REAP’s previous quantitative research to write a “mixed-methods” paper on LBCs in order to offer a more complete picture of this population of children.

As you’re preparing to conduct this research, consider the following questions:

- How do you think being left behind affects children? In terms of academics? In terms of mental health?

- Do you think being left-behind has larger impacts on certain groups of children? For example, will it have a larger impact on elementary school students than junior high students?

- Do you think the situation of LBCs is different depending on which parents migrate?

- How do you think outcomes differ between LBCs who have one parent at home and those who have no parents at home? How do you think a child’s situation changes when their second parent migrates?

- Do you think that surrogate caregivers are an adequate substitute for parents?

- What measures do you think could be taken to improve the situation of LBCs? Is this appropriate for all “types” of LBCs?

- Are left-behind children really worse off than other children in China’s rural areas? Should we focus on left-behind children, specifically, or all children in rural China?